Archaeology Blog

Put a Lid on it

Every artifact that is analyzed and catalogued as a part of the Wing Re-analysis project adds something to our knowledge about life at Poplar Forest through the ages. The individual attributes of an artifact, such as the type of decoration on a ceramic sherd or the position of a mold seam on a piece of bottle glass, provide evidence as to how and when the object was made, used, and discarded. Some artifacts provide more clues than others and archaeologists have a myriad of resources that help us examine the details of these artifacts and solve the mystery that each presents. A recent example of this process from the Wing project is the identification and analysis of this fragment of a glass fruit jar lid.

At first, we were quite baffled as to what this circular glass artifact was, how it was used, or when it was made, but the special details of this artifact helped to answer all of those questions.

Around the perimeter and inner section of the artifact are embossed numbers: “4. 62. DEC” and “22. 68. JAN” respectively. These types of markings on glass usually denote patent dates. Patents are publicly accessible documents and can be easily searched on the internet. In this case, we chose Google Patent search to try and hunt down the patents matching these dates. We searched for these dates as both 19th and 20thcentury dates (i.e. January 22, 1862 and January 2, 1962). Unfortunately, the numbers and months molded on this fragment did not correspond to any patents for glass products. This led us to believe that some information might be missing from these dates. For example, the numbers and months on this fragment might not go together, but are parts of separate dates.

Still, our search was not abandoned, we only changed tactics. Many of the objects that correspond to the broken bits we find in historical archaeological excavations were mass produced and some whole examples survive today. These complete objects never enter the archaeological record and are commonly sold in antique stores or become curated in private collections. As such, an internet search for “aqua glass 4. 62. DEC” returned the website called “Antique Fruit Jars” made by a collector of glass fruit jars and lids made in the 19th and early 20th centuries (“Antique Fruit Jars”). One of the fruit jar lids matched the color, form, and embossed dates of our artifact exactly (scroll to Lid #20). Suddenly, we learned what our glass artifact is and how it was used! This glass lid would be set over the rim of a jar and then fastened to it with a metal closure. In our research, we discovered several possibilities for this metal closure, such as a thumbscrew or Mason’s screw cap, which can be seen on the Society for Historical Archaeology Bottle Website. After finding more images of matching jar lids on the internet, we believe that our lid was most likely secured with a metal screw cap, as seen here.

In addition, there are eight full patent dates (i.e. “NOV 4. 62.”) embossed on the complete lid featured on the internet, including dates that match the fragments of dates on our artifact. We gained reasonable evidence from the website to suggest that the patent dates (and maybe the artifact itself) might be from the 19thcentury (1800s), rather than the 20th century (1900s). So, we searched for the patents again using full 19th century dates and found patents for each one. Here are links for two of them:

“Improved Fruit Jar,” November 4, 1862

“Improved Fruit Jar,” December 22, 1868

These eight patents relate to new or improved fruit jar types and closure methods, but none appear to include the invention of our style of fruit jar lid specifically. While these patents cannot provide an exact production date for the lid, the appearance of these dates on the artifact mean that this jar lid must have been made after the latest patent date.

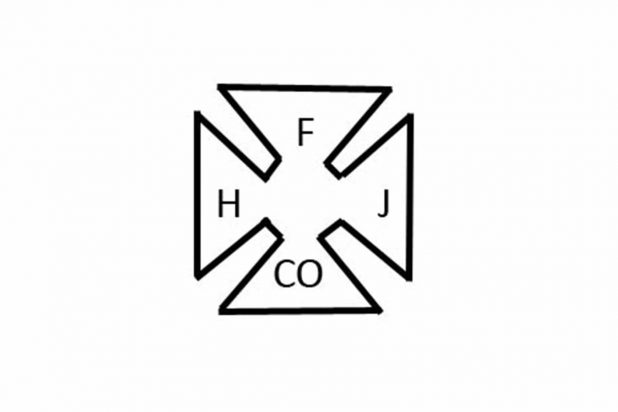

With the artifact identified and roughly dated, we turned to the Poplar Forest archaeology reference library and a book called Fruit Jars (1969) by Julian Harrison Toulouse, which explores the manufacturing history of glass fruit jars in the United States. A large part of this book is dedicated to a glossary of glass manufacturers and their marks. Embossed in the center of our lid fragment is a small portion of a cross shape with triangular wings, which could be part of a maker’s mark. The same cross shape appears in the center of the complete lid from the fruit jar website that matched the molded patent dates on our artifact. The fruit jar website attributes this lid to a “Hero” company, but gives no other information. Here, Toulouse’s book confirmed that the cross-shape was a signature mark of the Hero Fruit Jar Company. While many manufacturers used various styles of crosses in their marks, the one depicted on our artifact and the matching lid on the internet is a unique style named the “Hero Cross,” because it was designed specifically by the Hero Fruit Jar Company (Toulouse, 1969: 146).

A second book in our library, Bottle Makers and Their Marks(1971), also by Toulouse, helped to elaborate on the history of this glass company. The Hero Fruit Jar Company was based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and was originally named the Hero Glass Works. While the exact founding date for the Hero Glass Works is unknown, the earliest issued patent attributed to the company dates to 1856. Toulouse notes that the Hero Glass Works often embossed many of its patent dates on its products, even if they did not apply to the specific product, as another form of trademark or brand recognition (Toulouse, 1971: 249).

Turning back to the company’s official marks, Toulouse asserts that the “Hero Cross” was first used by the Hero Glass works in 1882. However, in 1884 when the company changed its name to the Hero Fruit Jar Company it also modified its logo to match, adding the initials “H F J Co” to the cross shape—one initial in each wing of the cross. Toulouse’s research determined that this mark was only used from 1884 to 1900, and the Hero Fruit Jar Company ended production of jar lids in 1909 (Toulouse, 1971: 249-250). Fortunately, our lid fragment includes enough of the bottom wing of the cross to see the initials “CO” in it. This means that our jar lid was made sometime between 1884 and 1900!

So what can all of this information about a fruit jar lid tell us about Poplar Forest? First, it provides us with a clear example of an activity—in this case, canning and preserving fruits—happening at Poplar Forest in the late 19th century. Moreover, it gives us a better understanding of when the sediment layer, or context, associated with this artifact was deposited. Because the lid could not be thrown away before it was made, this artifact and its context must have been deposited in the ground during or after 1884.

In this way, a fragment of glass, like each artifact we analyze, becomes a piece of information that helps us write a more complete history of Poplar Forest.

References

“Antique Fruit Jars.” http://users.rcn.com/donlav/fruit-jars/index.htm

Lindsey, Bill. 2012. “Bottle Finishes and Closures, Part III: Types of Bottle Closures, Fruit/Canning Jar Closures.” http://www.sha.org/bottle/closures.htm#Canning%20Jars

Toulouse, Julian Harrison. 1969. Fruit Jars. Camden, NJ: Thomas Nelson & Sons and Hanover, PA: Everybodys Press.

Toulouse, Julian Harrison. 1971. Bottle Makers and Their Marks. Camden, NJ: Thomas Nelson & Sons.