Archaeology Blog

Artifacts from the Carriage Turnaround: the 20th century

Over the last 3 years, archaeologists at Poplar Forest have excavated the Carriage Turnaround to understand what it might have looked like during Jefferson’s era and what changes the later owners made. We’ve finished cataloging the Carriage Turnaround artifacts and I’d like to highlight several of the interesting items we’ve seen from various periods of occupation at Poplar Forest. Overall, the Carriage Turnaround held less material than our other recent projects like the Wing and the Clumps of Trees and Oval Planting Beds (COB). This is the first of three posts, which will work backwards from the mid-20th century to Jefferson’s time. Today I’m going to show two objects from the Carriage Turnaround that I think might have special interest for those who grew up in the 20th century.

Poplar Forest was owned through the early 20th century by Christian S. Hutter until 1946, when he sold it to Lynchburg lawyer James Watts and his wife Sarah. The couple found it a privilege to live at Poplar Forest with their three children, James III (Jimmy), Key, and Stephen. The Watts not only lived at Poplar Forest but also used it as a dairy farm, which it remained for the next 3 decades. According to oral interviews, they used the Northeast area of the turnaround as parking for their automobiles (Chambers 1989). As we excavated, we found artifacts from the Watts era in the ground.

Poplar Forest ca. 1943 [Poplar Forest 1989.012P]

Image taken by C.S. Hutter of the Turnaround, just a few years before the Watts arrive. The Turnaround looks much like this until 2012 when the boxwoods were removed.

We discovered 2 pencil sharpeners made of an early Bakelite or Bakelite-derived plastic in the Carriage Turnaround. One sharpener was greenish with a round shape, and the other brownish in a rectangular shape. Bakelite is a trade name for a material composed of phenol formaldehyde resin, a thermoset plastic, which means it can be molded or cast into a shape, but it will not melt or deform out of that shape (unlike thermoplastics, which do deform with heat. Many of our modern plastics are thermoplastics). Bakelite was the first true synthetic plastic. After Leo Baekeland patented the material in 1907 it quickly became popular for many uses due to its resistance to chemicals, heat, rot, and wear (Crespy et al 2008). In 1927, Catalin bought the Bakelite patent and made many brightly colored plastic consumer goods, including pencil sharpeners, with their version of Bakelite, called Catalin (Cycleback 2013). When this early plastic ages, the colors tend to shift, so it is possible these sharpeners are not the original colors they once were (Leshner 2005: 11). This pencil sharpener is not likely to have been made later than the 1950s, around the time when the Watts and their children moved to Poplar Forest. Bakelite/Catalin began to lose popularity to other newfangled plastics after World War II mainly due to the expense of the resin production process compared to the new thermoplastics (Crespy et al 2008).

Bakelite/Catalin pencil sharpener circa mid-20th century, carved with a “W” by Jimmy Watts.

At some point someone carved an initial into the side of the rectangular pencil sharpener, which is pictured above. Our first guess was that this initial could be a “W” carved by some member of the Watts family. Subsequent inquiries with members of the Watts family confirmed it was indeed meant to be a W! As for the unknown carver: we now believe he/she was none other than Jimmy Watts, the eldest child of James and Sarah Watts (Stephen Watts pers comm: 2014). Archaeologists rarely know for sure exactly who modified and/or used artifacts, so it is a real treat to identify to whom this sharpener belonged. This sharpener was found above a gravel layer along the edge of the entrance road just before it leads into the turnaround. The (unmarked) round greenish sharpener came from among the roots and leaf litter of boxwood shrubs that were planted around and within the center of the carriage turnaround.

Most of a Pal-Ade bottle, circa mid-20th century, recovered from the Turnaround and mended.

The second 20th century artifact I’d like to highlight is a special soft-drink that was local to the Virginia region. This Pal-Ade bottle came up out of the topsoil layer around the boxwoods. We found most of the bottle and mended enough to read some of the red and white applied color label. Pal-Ade was a fruity soft-drink with no carbonation that was apparently pasteurized. Yes, no carbonation means no bubbles or fizz in the “soft drink!” The bottle does not mention the flavor, but Pal-Ade seems to have come in 2 flavors of sugary pasteurized goodness: orange and grape. The trademark names Pal and Pal-Ade first appeared around 1944-1946 (Odell 2007) and Pal-Ade appears to have been sold through the middle to third quarter of the 20th century. Pal-Ade was bottled in several locations around Virginia, from Marion and Newport News to Washington, DC (Lee 2008; Odell 2004; NNHS 2005). Now only the bottles, bottle collectors, and those who enjoyed it years ago can speak to its existence. It may be a bottle from the Washington, DC plant since there is no indication on the bottle of being bottled in Marion or Newport News. I like to think of the Watts kids sitting on the north portico drinking some Pal-Ade!

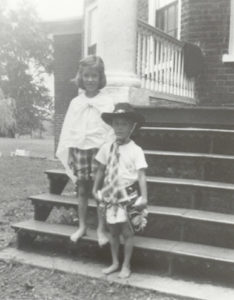

Key and Stephen Watts as children standing on the cast-iron steps of the North Portico, circa 1950s.

[Poplar Forest 1995.003]

Check back soon for “Artifacts from the Carriage Turnaround” Part 2: Regarding the Hutters!

-E

SOURCES:

1989 Chambers, S. Allen

“Interview of James O. Watts.” May 10, 1989. With James O. Watts, Stephen Watts and Sarah Giles present

2008 Crespy, Daniel, Marianne Bozonnet, and Martin Meier

“100 Years of Bakelite, the Material of a 1000 Uses.”AngewandteChemie International Edition.Vol 47: 3322–3328. Issue 18, April 21, 2008

2013 Cycleback, David

“Bakelite and catalin: Collectible early plastics.” Looking at Art, Artifacts and Ideas. Posted 1/31/2013. URL: http://cycleback.wordpress.com/2013/01/31/bakelite-and-catalin-phenol-formaldehyde-identifying-the-popular-early-plastics/

2008 Lee, Joseph III

“Marion Bottle”. The History of the Soda Bottlers of Southwest Virginia, Northeast Tennessee, and Mercer County West Virginia. Tazewell Orange.com URL: http://www.tazewell-orange.com/marionbott.htmlAccessed 10/5/2014.

2005 Leshner, Leigh

Collecting Art Plastic Jewelry: Identification and Price Guide.Krause Publications. 256 pages

2005 Newport News High School Class of 1965

“Pal Bottling Company.”Our Old Stomping Grounds N-R. Page created 09/16/2005. URL: http://nnhs65.com/pal.htmlAccessed 10/5/2014.

2004 Odell, Digger

“SODA AND CARBONATED BEVERAGE TRADEMARKS 1940s.” Digger Odell Publications. URL: http://www.bottlebooks.com/carbonated%20beverages/carbonated_beverage_trademarks%201940.htm Accessed 10/5/2014.

Poplar Forest image 1995.003. Depicting Watts Children.

Poplar Forest image 1989.021. Depicting Turnaround c. 1943 by C. S. Hutter

2014 Watts, Stephen

Personal email communication regarding sharpener and blog post. 11/13/2014.