Archaeology Blog

Artifacts from the Carriage Turnaround: the Long Hutter (19th) Century

“So the ages have their dress and undress;

And the gentlemen and ladies of Victoria’s time are satisfied with their manner of raiment…”

W.M. THACKERAY — “THE ADVENTURES OF PHILIP”

Today the second part of our artifact series on the Carriage turnaround will highlight several Hutter period artifacts. The Hutters owned Poplar Forest for 118 years beginning with Emily “Emma” Cobbs’ marriage to Edward Sixtus Hutter in 1840, and continuing to 1946 when James Watts bought the property. The pair are pictured below. Emma’s parents, William and Marian Cobbs were quite happy to give E.S. Hutter control of Poplar Forest’s estate management upon his marriage to their daughter. The Cobbses continued to live with Edward and Emma at Poplar Forest to the end of their lives. The untimely deaths of Emma and Edward from illnesses in the 1870 and 1875 respectively, left behind their children and grandmother Marian Cobbs. Not long after the passing of Marian Cobbs in 1877, Hutter descendants began renting Poplar Forest to tenants until it came under the care of youngest son Christian Sixtus Hutter in the late 19th and early 20th century (Marmon 1991: 88, 96-97). Little is known about the tenants from this time period. During C.S. Hutter’s ownership, Poplar Forest was mainly used as a “summer house” and farmed by tenant farmers who lived in other houses on the property.

Most of the known Hutter-era occupation materials in the Carriage Turnaround are ironstone table and teawares and later transfer printed earthenwares. These are artifacts of the Victorian table, but not objects you can really pin down to usage by individuals. Therefore, while cataloging the turnaround artifacts, I was delighted to find several probable Hutter-era personal artifacts in the Carriage turnaround material.

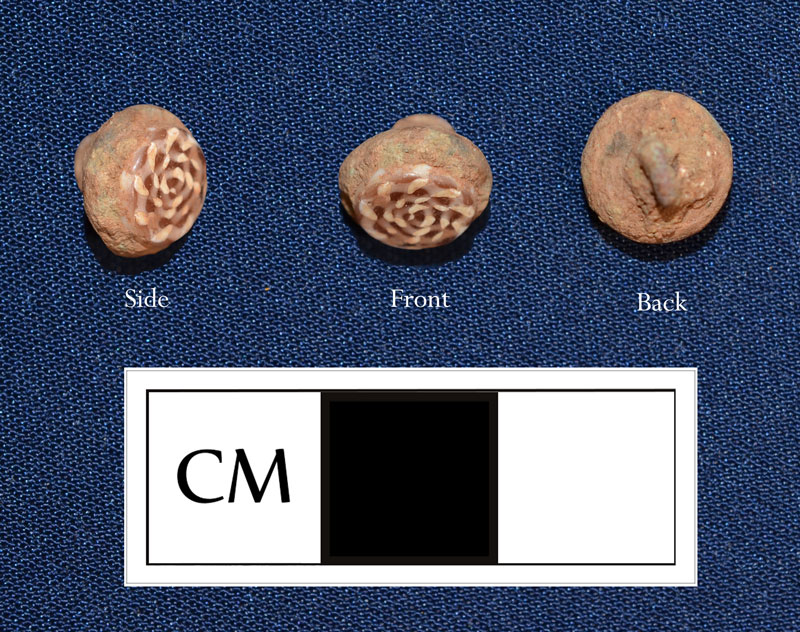

First up, we unearthed a waistcoat button from under the boxwood rootmat in the eastern part of the turnaround:

This button is composed of a flat-faced glass accent with two canes of colorless or slightly pink/lavender glass and opaque white glass twisted into a spiral, set in a cast or plated(?) copper alloy setting with a wire-eye. The copper setting may have had a wavy decorative edge to it. The button had not been cleaned at the time of the photo above, but it will be sent out for a cleaning by a professional conservator. It is likely to be a waistcoat button due to its small size, less than 9 mm in diameter. Glass-set waistcoat buttons such as this one were popular between 1850-1880 (Hughes & Lester: 155).

Who could have worn a waistcoat? Waistcoats were close-fitting vest-like garments worn under jackets, like the one Edward Sixtus Hutter is wearing. Mr. Hutter’s photograph was taken sometime between the 1840s to 1870s, well within the given time range of these types of buttons. We can’t tell from the sepia tone of E.S. Hutter’s image if it was this very waistcoat, but this button would have featured similarly on some man’s torso at Poplar Forest during the latter half of the mid-19th century. Waistcoats tended to be a male-gendered clothing article, and one of the most colorful parts of the Victorian male wardrobe (Shannon 2006: 76-77). This button is one of the few items from the turnaround we can say was used by a specific gender. Perhaps with these pretty glass buttons, the wearer intended his waistcoat to be an expression of his own unique taste within the strict dictates of Victorian male fashion.

A similar button made with green and white cane twist can be seen in Hughes and Lester’s Big Book of Buttons (plate 59, button 14). A search of Pinterest also yielded one other similar example, pictured above (R.C.Larner Buttons 2014). Collectors today call buttons like this with glass centers and metal rims by the fancy term of “jewels.” An example of a waistcoat with “jewel” buttons can be seen in the below vest from the Metropolitan Museum collections. (I’ve added a button detail inset). These glass buttons don’t have swirls like ours does, but they are similar in form. This waistcoat dates from the 1860s and is titled a “wedding waistcoat.” Waistcoats were not just for weddings though; they were an integral part of the gentleman’s wardrobe. No waistcoat? Not a gentleman! Without a waistcoat on, a gentleman was considered “undressed”, even in his own home. Note that “undressed” by the Victorian definition often meant that one was wearing clothing to work in for an occupation (Victoriana 2013). Showing oneself in polite company in “undress” implied a person was not a proper gentleman, or was of a lower socioeconomic class.

Waistcoat with similar type of glass button embellishment (c. 1860s) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collections

The second artifact I’m highlighting today is another gendered clothing fastener, which could have belonged to one of the female occupants of the Hutter household. It is from a corset busk and would have been part of the metal fasteners on the front of corsets that provide rigidity to the front of the undergarment. Several pieces of busk hooks and eyes were recovered from the turnaround, indicating at least one or more busks were discarded in this area. Other fragments have been recovered from the Clumps and Oval Beds project and the Wing of Offices. This type of busk was a dividing busk, composed of two stiff steel ribs with metal hooks and eyes, which enabled better ease of removal. An example of a dividing busk corset from the Met Museum collections is also shown below. The Met museum example dates to 1860, but dividing busks were available by the 1830s; this specific type of “slot and stud” fastening busk was patented in 1848 and in regular use from the 1850s until the early 20th century [Steele 2001: 43].

Emma Cobbs Hutter could potentially have worn corsets with a steel dividing corset busk during her lifetime at Poplar Forest from adolescence in the 1830s until her death in 1870. The gown shown in the above image of the Hutters and the usual female fashions of the period would have required a corset underneath as a foundation to obtain the proper silhouette. Like the waistcoat to a gent, no Victorian woman of respect would have been caught in public in a dress without a corset underneath to give her the proper figure. Women saw corsets as a necessity to construct an ideal of feminine beauty and respectability (Steele 2001: 35, 42).

Basic mid-Victorian era mass-market manufactured corset with dividing busk using “slot and stud” fasteners. From Metropolitan Museum collections, c. 1860s

We know that there were enslaved women living at Poplar Forest during the Hutter era. It is certainly possible this busk is from one of the working women in the Hutter household. Many working-class women wore corsets, and free black women in America also adopted the corset. So did some enslaved women (Steele 2001: 49). If any enslaved women at antebellum Poplar Forest wore corsets, they were probably among the house workers. Unlike colorful waistcoats, corsets were almost always made up of plain white fabric from 1800 until the 1870s (Steele 2001: 39). The only real differences between Emma Hutter’s corsets and those of house slaves or tenant wives and daughters nearby would have been in the quality of fabric and the fit and/or comfort.

Although the waistcoat was meant to be visible and the corset itself was meant to be hidden (yet create a visible silhouette), these were both garments that constructed an image of an ideal man or woman of the leisure class. Without these garments on in polite Victorian company the individual might as well have been considered naked. People of the working classes also wore these garments although they may have donned them only for church or special occasions. The working class individual would also have been likely to own fewer, or just one waistcoat or corset. Given the status of the inhabitants of Poplar Forest, it is likely these were garments owned by individuals in the Hutter family.

Thanks for reading and check back soon- Part three of our Carriage Turnaround artifact discussion will get into the Jeffersonian era!

-Esther

Sources Cited:

1993 Hughes, Elizabeth and Shannon Lester

The Big Book of Buttons.The J.S. McCarthy Company. Augusta, Maine.

1991 Marmon, Lee

Poplar Forest Research Report, Patt I.

2006 Shannon, Brent

The Cut of His Coat: Men, Dress, and Consumer Culture in Britain, 1860-1914.Ohio University Press.

2001 Steele, Valerie

The Corset: A Cultural History. Yale University Press. New Haven, CT.

1861 William Makepeace Thackeray

“The Adventures Of Philip.” Harper’s Magazine, Vol 23: June To November 1861. Page 689. URL: http://books.google.com/books?id=shIwAAAAMAAJ

2013 “Dressing the 1860s Gentleman.” Victoriana. URL: http://www.victoriana.com/how-to-dress-victorian/

Images:

Edward and Emma Hutter. Owned by Poplar Forest

2014 R.C. Larner Buttons”Two Mid-19th C. Glass Overlay Waistcoat Jewel Buttons “ Waistcoat Jewels (Pinterest Board) URL: http://www.pinterest.com/pin/477240891735199629/

Corset. Manufacturer: Langdon, Batcheller & Company. (American, founded 1865) The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Brooklyn Museum Costume Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of the Brooklyn Museum, 2009; Gift of E. A. Meister, 1950 Online URL: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/175651?rpp=30&pg=4&ft=corset&when=A.D.+1800-1900&pos=93

“Wedding waistcoat.“ The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of The Misses Mary L. and Katherine Gardner, 1958 Online URL: http://www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/91082?rpp=30&pg=2&ft=waistcoat&when=A.D.+1800-1900&pos=42