Archaeology Blog

Blowing Smoke: A Presidential Campaign at Poplar Forest

Anthropomorphic clay tobacco pipes, also sometimes called figural pipes or face pipes, were a popular type of commemorative souvenir in the nineteenth century. Pipe manufacturers often made pipes depicting the faces of famous political and cultural figures including George Washington, Queen Victoria, and Charlotte Bronte among many others. One particularly collectible subset of figural tobacco pipes is that of President pipes (Bell 2004). Although some of the pipes included in this category are more commemorative in nature, such as those of George Washington, most President pipes were made and distributed during presidential campaigns in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century (Pfeiffer et al 2006). One such pipe featuring the likeness of Franklin Pierce, the 14th President of the United States, was recovered in 1994 from excavations at the Wing of Offices near the main house at Poplar Forest. Elected by a landslide during an era of national instability and increased tensions, Pierce quickly became seen as a weak leader that caused one of the major precursor events leading to the American Civil War.

Figure 1: Franklin Pierce pipe from Wing of Offices excavations, four views. Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest Department of Archaeology.

The Franklin Pierce pipe in the archaeological collection at Poplar Forest is made from fired red clay coated in a clear lead glaze. The portrait of President Pierce’s face is fractured so that only the lower half of the face and part of the hair remains still connected to a short shank into which a detachable reed or wooden stem could be inserted for use. This pipe displays no evidence of use or burning. The shank is marked with FRANK PIERC on the left side and PRESIDENT on the right side. Beneath the word president are stamped the letters CP, which may refer to the manufacturer but remains unidentified. A pipe similar to this variant has been identified from Fort Sanders, Wyoming (1866-1882) (Pfeiffer et al 2006:14).

Figure 2: Franklin Pierce pipe from Wing of Offices excavations, close-up views. Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest Department of Archaeology.

Anthropomorphic reed-stem tobacco pipes were produced in multiple factories in the nineteenth century, but compelling evidence suggests that the Franklin Pierce pipe from Poplar Forest and similar Stummelpfeifen (“stub pipes”) originated in the town of Uslar, Germany. Uslar and Grossalmerode, a town only about 60 km distant, were hubs of German pipe production in the nineteenth century and the majority of their products were produced specifically for export to American markets (Pfeiffer et al 2006:5). An estimated 4.5 million pipe bowls were exported from Uslar to the US in 1845, increasing to about 11 million pipes by 1866 (Pfeiffer et al 2006:5). Records from Grossalmerode indicate that around 95% of their 1864-1866 sales were in wholesale trade to America (Pfeiffer et al 2006:6). In the late 1860s, the economic fallout of the American Civil War and a simultaneous increase in domestic pipe production reduced the demand for German-made pipes in the US (Pfeiffer et al 2006:6-8).

Figure 3: Uslar, Germany is located in southern Lower Saxony. Grossalmerode (or Großalmerode) is approximately 60 km away in Hesse, Germany.

Some American pipe manufacturers produced crude imitations of Stummelpfeifen by using the imported German figural pipes to cast molds for their own factories, but these copies are usually distinguishable by a wider angle between shank and bowl, a blurring of fine details, and the presence of visible mold seams running vertically down the center of the face (Pfeiffer et al 2006:7). The pipe in the Poplar Forest collection exhibits sharp detailing in Pierce’s hair and collar and faint mold seams only along the top and bottom of the shank, thus suggesting it was cast from an original mold. A well-known center for red clay pipe production in central Virginia was Pamplin, in Appomattox County (only about 40 miles, or 64 km, from Poplar Forest). Local tradition states that pipe making there began as early as the 1740s and continued as a mainly home-based industry until the Pamplin Pipe Factory was established in 1878 (Virginia DHR). Early Pamplin pipe makers used local clays to make pipes of over 70 different styles; usually a dark red product finished with beeswax or mutton tallow (Virginia DHR). The only recognized novelty pipe from the Pamplin production area is called Type AK and is shaped like a tomahawk, with the bowl forming the “blade” and the stem the “handle.” A likeness of George Washington appears on one side, with WASHINGTON stamped above while the other side contains the profile of a Native American with POWHATAN above (University of Missouri). No tobacco pipes traditionally called ‘face pipes’ have been attributed to the Pamplin pipe makers.

The major ports of entry for German pipes into the United States were New York, Baltimore, and New Orleans, although some other ports in the American South were regularly used (Pfeiffer et al 2006:8). Distribution from these centers of import was wide and effective as demonstrated through archaeological recovery of German face pipe fragments at sites throughout the country. Pipes representing three campaigning or sitting American presidents have been identified as varieties from the Uslar and Grossalmerode listings: Zachary Taylor (1849-1850), Millard Fillmore (1850-1853), and Franklin Pierce (1853-1857). There are no known German reed-stem pipes depicting James Buchanan (1857-1861) or Abraham Lincoln (1861-1865), thus implying that the Franklin Pierce pipe was the last of the President pipes series made in Uslar (Pfeiffer et al 2006: 8).

Figure 4: President Franklin Pierce official White House portrait, George Peter Alexander Healy, 1852. White House, image source here.

Franklin Pierce was born in 1804 to Benjamin Pierce and Anna Kendrick (Holt 2010:5). While attending Bowdoin College, he honed his natural skill in public speaking and became a fervent devotee of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party (Holt 2010:10). Once elected to the US House of Representatives in 1832, and later the US Senate in 1837, Pierce faithfully voted the party line on almost all issues (Urofsky 2000:176). Many of his closest friends and allies in Congress were pro-slavery southerners, and Pierce came to sympathize with their views, rigidly upholding rights to the preservation of personal and property rights (Miller Center, Urofsky 2000:176). While in town, he enjoyed the night life of Washington DC (perhaps a little too much) and Pierce’s drunken antics were often the topic of conversation in the nation’s capital (Holt 2010:7-8, Miller Center). Eventually, Pierce cleaned up his act and married Jane Appleton, a deeply religious woman and advocate of the temperance movement. Possibly due to Jane’s influence, Franklin Pierce resigned the US Senate in 1841 and returned to New Hampshire, where he became a popular and successful trial attorney (Miller Center).

Figure 5: Daguerreotype of Jane Appleton Pierce with her youngest son Benjamin ‘Benny’ Pierce, c.1850. Benjamin was killed in a train accident in Andover, MA two months before his father’s inauguration. White House Historical Association, image source here.

In 1844, Pierce managed the New Hampshire branch of James K. Polk’s successful presidential campaign. He was rewarded three years later with a commission as a Brigadier General in the US Army; commanding over two thousand men in the Mexican-American War, despite his complete lack of military experience (Urofsky 2000:176). While serving under the command of General Winfield Scott (known to his men as “Old Fuss and Feathers” for his insistence on discipline and protocol) at the Battle of Contreras, Pierce was thrown from his horse, breaking his leg and causing him to pass out. While his leg eventually healed, this episode earned him the nickname “Fainting Frank” from resentful soldiers (Miller Center).

Figure 6: Democratic presidential candidate Franklin Pierce, sometimes called ‘Handsome Frank’, shown in brigadier general’s uniform, photographer unknown, 1852. New Hampshire Historical Society. Figure 7: Whig presidential candidate Winfield Scott, photographer unknown, 1852.

By the time of the nominating conventions for the presidential election of 1852, the Democratic party was threatening to split over the issue of slavery. Southerners wanted slavery to be allowed in the expanding new US territories while an increasing number of northerners supported abolition (Hodder 1913:72-73). The Democratic Nominating Convention was deadlocked in choosing a candidate because each man nominated faced strong opposition from one faction or another within the party (Miller Center). Finally, after 49 ballots, they settled on Franklin Pierce, a relatively obscure man with an undistinguished voting history, a military record on his resume, and a sociable demeanor that was not forceful enough to upset any one faction (Holt 2010:137, Miller Center). Most importantly, Pierce was a pro-slavery northerner and could be molded into whatever was needed to overcome the candidate of the opposing Whig party. Coincidentally, the Whig party nominated Pierce’s former commander, Winfield Scott, two weeks later.

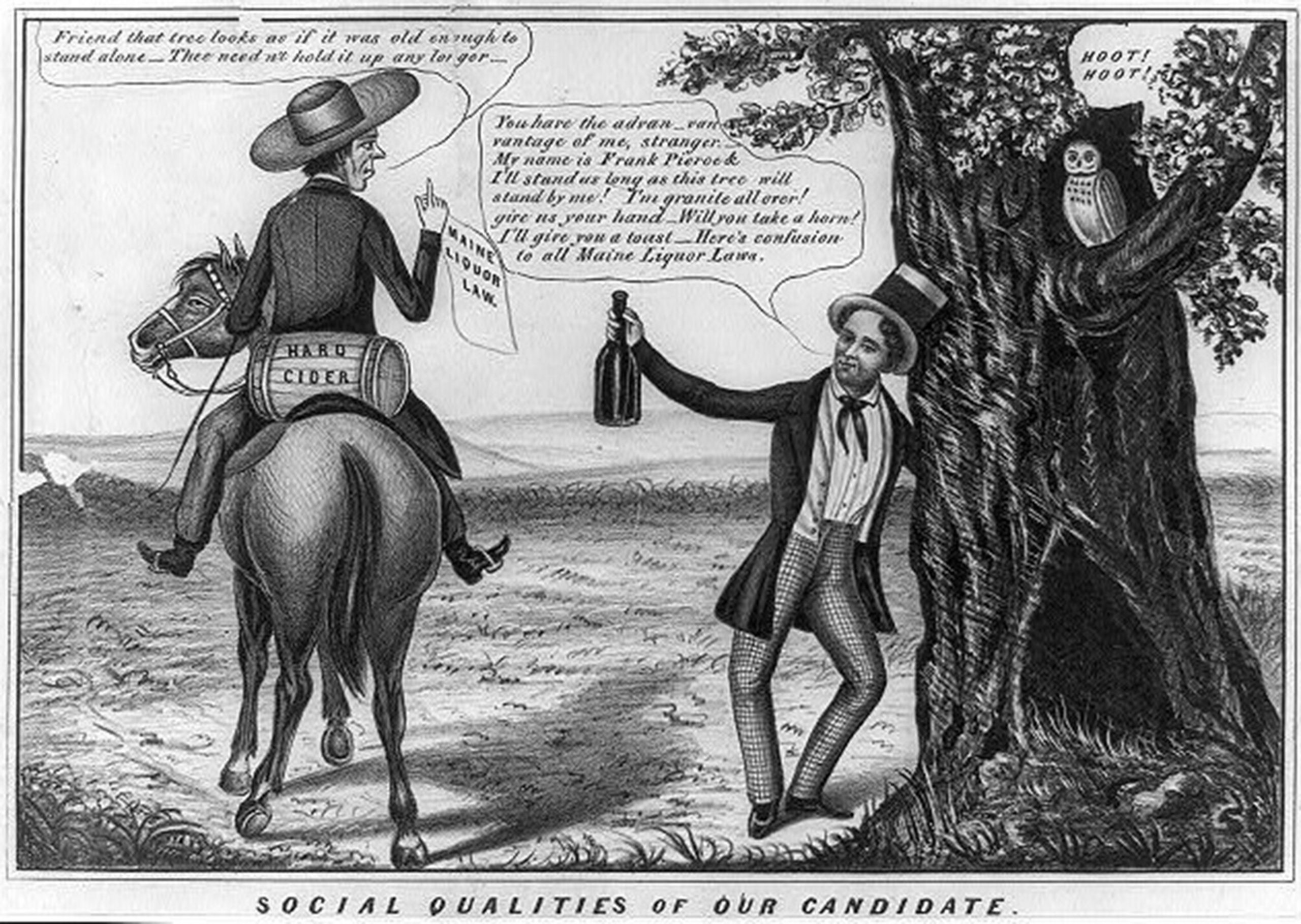

In the campaign of 1852, both the Democrat and Whig parties ran on very similar platforms except for the issue of slavery, which neither side wished to engage for fear of alienating voters (Person 2009:2 ). So instead of policy, the race focused on the personal lives and characters of the two men vying for president. Whigs revived the old stories of Pierce’s drunken youth and accused “Fainting Frank” of cowardice during his military service (Miller Center). Political cartoons sharply contrasted the two men; in one cartoon, Pierce is equated to a mouse scurrying through the New Hampshire mountains while Winfield Scott is a bobcat lying in wait. In other cartoons, a drunken Pierce leans against a tree or hangs back from battle while the courageous Scott leads troops into the fray.

Figure 8: Social Qualities of Our Candidate: Political cartoon mocking Franklin Pierce’s alcoholic reputation, published by John Childs, 1852, United States Library of Congress. (Right) A Bad Egg: Political cartoon encouraging the public perception of Winfield Scott as an advocate of anti-slavery interests and the pawn of powerful abolitionist William Seward, published by Nathaniel Currier, 1852, United States Library of Congress.

Of course, the Democrats fired back at the Whigs with cartoons of their own, depicting Scott as a fat turkey trying to monopolize the road or as a pawn of the powerful abolitionist William Seward. To further contrast the men and combat the unmanly allegations against Pierce’s character, Nathaniel Hawthorne (a college friend of the candidate) penned Life of Franklin Pierce, emphasizing Pierce’s masculine charisma throughout .

“His language always attracts the hearer. A graceful and manly carriage, bespeaking him at once the gentleman and the true man, a manner warmed by the ardent glow of an earnest belief, an enunciation ringing distinct and impressive beyond that of most men, a command of brilliant and expressive language and an accurate taste, together with a sagacious and instinctive insight into the points of his case, are the secrets of his success.” (Hawthorne 1852:60)

Hawthorne molded Pierce’s biography to fit the ideal Democratic candidate; he illustrated humble beginnings, an unpretentious youth, life-long party loyalty, and a solidly middle-class life that would aid in the candidate’s “identification with the democratic people, for it made the candidate one of them” (Roggenkamp 2008:366-367, Person 2009:2).

During this era, candidates for president rarely went on the campaign trail for themselves and instead relied heavily on the propaganda machines of their powerful political parties to circulate their names and platforms and garner support from the electorate (Bourdon 2016). Winfield Scott was only the second major party presidential candidate to go on a speaking tour to meet voters, but this plan backfired and his opponents were able to paint his electioneering as a “naked attempt to obtain power” (Bourdon 2016). Face pipes, such as the one found at Poplar Forest, were one way for political parties to spread awareness of their contender’s candidacy. In a century where smoking was an almost universal habit, the use of a political pipe in a social setting was equivalent to wearing a modern-day campaign button.

In 1852, Poplar Forest was the home of Edward and Emma Hutter, their children, and Emma’s mother Marian Scott Cobbs. As a male ‘propertied freeholder’ in the state of Virginia, Edward Hutter was eligible to vote in the 1852 election (Marmon 1991:67). He was the son of a prominent newspaper publisher in Easton, Pennsylvania (Marmon 1991:64). After a decade of service in the US Navy, he retired to Lynchburg and took up the life of a southern slave-owning planter by 1842 (Marmon 1991:66). Both the Democrat and Whig parties supported the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, but Pierce was more openly sympathetic with the slave-owning electorate (Miller Center). This must have struck a chord with Edward Hutter who was also a pro-slavery northerner. However, Edward Hutter was a former military man himself and may have sympathized with the experienced General Scott. Surviving records do not tell us how Edward Hutter felt about the presidential candidates or for whom he voted in the 1852 election, but the recovery of the Franklin Pierce pipe from Poplar Forest demonstrates that the race had at least some presence in Bedford.

However Edward Hutter chose to cast his vote, Franklin Pierce was elected as the 14th President of the United States after what one contemporary newspaper labelled the most “ludicrous, ridiculous, and uninteresting presidential campaign ever” by an overwhelming majority (Miller Center). In an election where 69.6% of eligible voters cast ballots, only four of the thirty states went for Scott (Vermont, Massachusetts, Kentucky, and Tennessee), making Pierce the youngest president to date (Miller Center, American Presidency Project.2016).

The hope of the Democratic party that Pierce’s election would ease sectional arguments amongst Americans was, sadly, not to pass. The loss of his only surviving child in a train accident just before his inauguration left Pierce somber and distracted during a time when the country desperately needed a unifying, forceful leader (Urofsky 2000:178). Instead, Pierce appointed politicians with extreme viewpoints to cabinet positions and allowed himself to be pressured into actions that alienated his moderate base (Miller Center, Urofsky 2000:179). Pierce’s most notorious blunder was to sign the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, allowing voters in a new state to determine the question of slavery for themselves (Miller Center, Urofsky 2000:180-182). People on both the pro-slavery and abolitionist sides of the debate flooded into Kansas, kicking off a multi-year period of unrest and violence now known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’ (Miller Center, Urofsky 2000:182-183).

The Pierce presidency has long been maligned in the historical literature; portraying the president as unqualified, overwhelmed, and inept and blaming Pierce’s weaknesses for accelerating America on the course towards civil war (Miller Center). One historian has summarized the prevailing view as follows:

“Franklin Pierce was an honest man who had strong beliefs, but by the time he became president a good part of the country no longer shared his views…If we measure presidents by the way in which they lead the country in response to crises, then Franklin Pierce is a failure…When a civil war broke out in Kansas, the ineffectiveness of the men Pierce sent to the territory was overshadowed by the moral and political ineffectiveness of the president.” (Urofsky 2000: 184).

And yet, this was a pivotal time for the country; a time in which a strong leader sensitive to national tensions could have altered the way history played out. The Franklin Pierce pipe in the Poplar Forest archaeological collection is a tangible reminder of America’s enduring struggles and the tremendous responsibility placed in the voters’ hands each time we elect a president.

For More information on the Kansas-Nebraska Act and Bleeding Kansas, see the following:

Fort Scott National Historic Site, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm

Rawley, James A. 1969. Race and Politics: “Bleeding Kansas” and the Coming of the Civil War. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, Nebraska.

Watts, Dale E. 1995. How Bloody Was Bleeding Kansas? Political Killings in Kansas Territory, 1854-1861. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains, 18(2): 116-129.

References:

American Presidency Project, The. 2016. “Voter Turnout in Presidential Elections: 1828 – 2012”. Based on Lyn Ragsdale, 1998, Vital Statistics on the Presidency, Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press, 132-38. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/data/turnout.php

Bell, Max. 2004. Collecting American Face Pipes. Bottles and Extras, 52-54.

Bolster, W. Jeffrey. 2005. Franklin Pierce: Defining Democracy in America. New Hampshire Historical Society.

Bourdon, Jeffrey. 2016. Sweet Irish Brogues, Mellifluous German Catholics, and African Slaves Ignored: Winfield Scott’s Caricatured Presidential Speaking Tour in 1852. Ohio Valley History, 16(2): 41-59.

Chambers, S. Allen. 1998. Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest, Forest, VA.

Hawthorne, Nathaniel. 1852. Life of Franklin Pierce. Ticknor, Reed and Fields.

Hodder, Frank Heywood. 1913. The Genesis of the Kansas Nebraska Act. From the Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin for 1912. Madison, Wisconsin.

Holt, Michael. 2010. Franklin Pierce: The American Presidents Series. Henry Holt and Company, New York, New York.

Marmon, Lee. 1991. Poplar Forest Research Report, Part Two. Internal report for the Corporation for Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest.

Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. “Franklin Pierce: Impact and Legacy.” Accessed October 1, 2016. http://millercenter.org¬/president/biography/pierce-impact-and-legacy.

Person, Leland S. 2009. A Man for the Whole Country: Marketing Masculinity in the Pierce Biography. Nathaniel Hawthorne Review, 35 (1): 1-22.

Pfeiffer, Michael A., Richard T. Gartley, and J. Byron Sudbury. 2006. President Pipes: Origin and Distribution. Paper presented at the 63rd Annual Meeting of Southeastern Archaeological Conference in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Roggenkamp, Karen. 2008. Campaigning for the Literary Marketplace: Nathaniel Hawthorne, David Bartlett, and the Life of Franklin Pierce. American Transcendental Quarterly, 22(1): 365-379.

University of Missouri. 2016. “Pamplin Clay Tobacco Pipes”. Museum of Anthropology, University of Missouri. Accessed October 5, 2016. https://anthromuseum.missouri.edu/minigalleries/pamplinpipes/pamplinpipes.shtml

Urofsky, Melvin I. 2000. Franklin Pierce: 1853-1857. In The American Presidents: Critical Essays, Taylor and Francis, 175-184.

Virginia Department of Historic Resources. 2012. Pamplin Pipe Factory, Appomattox County: An Archaeological Preserve; A gallery of images selected and annotated by DHR in collaboration with The Archaeological Conservancy. http://www.dhr.virginia.gov/SlideShows/Pamplin/pamplinTitleSlide.html