Archaeology Blog

Cast of Characters Part II

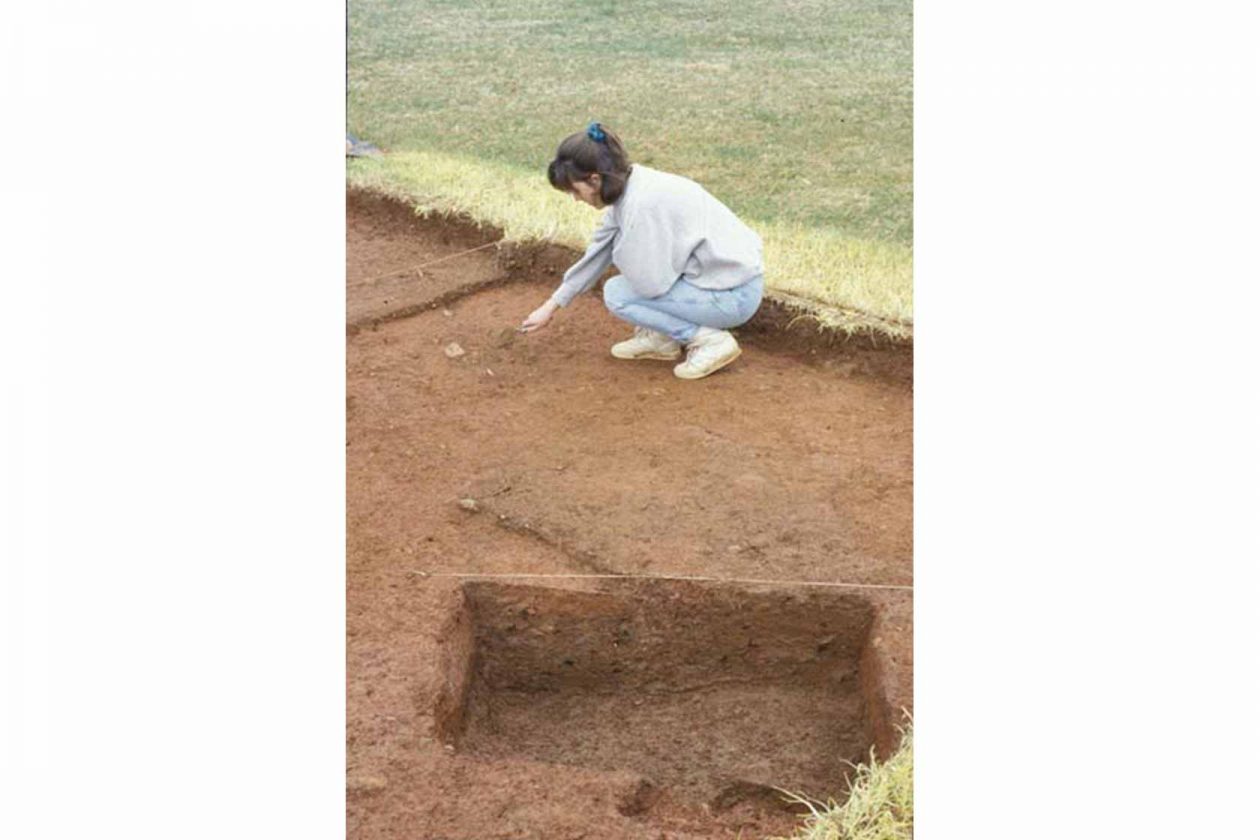

The Wing of Offices is also known interchangeably as the East Wing of Dependencies. This collection of outbuildings was an addition of the main house, and contained four separate rooms. The functions of these rooms are debated by academic scholars, but the possibilities include a kitchen, smokehouse, cook’s quarters, laundry, spinning/weaving room, dairy, or storage room.

While the functions of the rooms are up for debate, we can use written evidence from letters and other historical documents to try to identify some of the people who were likely to have worked within the dependency building. The following are brief biographies of the individuals, and their likely connections to the wing of offices.

Hannah (daughter of Cate Hubbard) was an enslaved resident of Poplar Forest who served as the main housekeeper and cook for Thomas Jefferson. Hannah could read and write, demonstrated by a single letter written to Thomas Jefferson (Hannah to TJ, November 15, 1818, MHi), and may have lived in the dependency wing while Jefferson visited (Heath, ND). If the third room is indeed the cook’s quarters, then this would likely be the place that Hannah resided when Jefferson was in residence. If the room was used as a laundry, she probably would have been employed there as well, washing for Jefferson and his family.

The last known reference to Hannah was made in a letter by Elizabeth Trist in which she describes: “… Hannah a Black woman who has care of the House…” (Elizabeth Trist to Nicholas Trist, Nov 28, 1822, DLC). It is not known whether Hannah was relocated after Jefferson’s death or if she remained at Poplar Forest with Francis Eppes’ inheritance of the property.

Burwell Colbert (1783-1827) was an enslaved resident of Monticello. He began work at an early age in the plantation nailery and was also skilled as a painter and window-glazer. Later in life, Burwell became the chief waiter and butler to Thomas Jefferson and accompanied him in most, if not all, of his travels. Thought of today as Jefferson’s “right-hand man”, Burwell supervised housemaids, waiters, and porters, and was highly admired by Jefferson and his family (Gordon-Reed 2008: 305). This admiration is especially clear when Burwell became ill in 1819 due to a bowel obstruction. Concerned granddaughters wrote about his health, and described how much he meant to Thomas Jefferson and their family in their correspondence (Cornelia to Virginia, 1819, NcU; E. W. R. to M. R. July 28, 1819, ViU; E. W. R. to Virginia Randolph, August 4, 1819, ViU).

At Monticello Burwell was tasked with keeping hold of the keys, regulating the contents of locked rooms, and responding to the bell system (Stanton 2000: 120-1). In 1821, Jefferson’s granddaughter Cornelia wrote about her harrowing trip to Poplar Forest, where upon arrival, overseer Joel Yancey (who held the keys) was not available to open the house. Burwell had to force his way through the front door because Jefferson, Ellen, Cornelia, and Burwell himself had essentially been locked out (Cornelia to Virginia, April 22, 1821, NcU).

Israel Gillette was a slave who was trained as a driver and would accompany Jefferson and his granddaughters on various trips, such as to Natural Bridge. While at Poplar Forest, he acted as chief steward during Burwell’s sickness and likely had direct connection with the wing of offices during this time. “I must not forget to tell you that Israel has shown during B.’s illness–has kept himself as clean and genteel as possible and in the pride of being chief waiter has followed Miss Edgeworth’s Hamilton’s rules of doing everything in its proper time, putting everything to its proper use, and everything in its proper place, with as much exactness as if he had studied them with every desire of edification.” (Ellen Wayles Randolph to Martha Randolph, July 28th, 1819, ViU). At Monticello, Isreal had dual roles of house servant and working in the stables. He would serve as postilion (an individual who rides the left horse of the front most pair pulling a carriage) on trips to Poplar Forest, and continued with household tasks during their stay (Stanton 2012: 161).

Bess was an enslaved resident of Poplar Forest who was employed in the dairy to make butter and was also employed in spinning textiles. Thomas Jefferson wrote of Bess in his instructions to Jeremiah Goodman: “Bess makes the butter during the season, to be sent to Monticello in the winter. When not engaged in the dairy, she can spin coarse on the big wheel”(TJ to Goodman, Instructions December 1811). Although this reference predates the construction of the wing (1814), several artifacts were recovered from the site which indicates spinning/ weaving activities.

One of the rooms in the wing of offices may have been utilized as a dairy, or perhaps a spinning/weaving room, and therefore it is possible that Bess (or another skilled person) may have been working in some capacity within the wing.

The “Tidy Mulattoe Girl” was a young enslaved girl that brought gifts over to Poplar Forest from a neighboring plantation owned by Richard Walker. Jefferson and his granddaughters had established a relationship with their neighbors here in Bedford County, particularly with Mrs. Walker, the mistress of the plantation. Mrs. Walker is described as being very generous and friendly and would send an enslaved girl over with various gifts to Poplar Forest. Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen accounts that “About once a week we see arrive a tidy mulattoe girl, with an apron as white as snow, & a nice little basket with a napkin thrown over it, in her hand. Sometimes fruit of different kinds, melons, apples, ripe peaches, etc. Then again vegetables, and on one occasion cake and sweet meats…. and I have felt quite ashamed to dismiss her so often unrewarded. There are in fact two of them, but one comes oftener than the other” (Ellen to Martha, August 24, 1819, ViU). These girls probably would have delivered the food items to Hannah, and possibly spent time talking with her or other slaves working in the wing, passing along news between the two plantations.

Nace Hubbard was a slave born in 1773, as property of Jefferson’s father-in-law John Wayles. Following the death of their parents, Nace and his two siblings became foster children of James Hubbard (at Poplar Forest, James was a headman and later became the hogkeeper). Nace lived primarily at Poplar Forest, and served in various roles including headman and gardener.

Nace was well regarded by Thomas Jefferson, who referred to him as the best headman Poplar Forest ever had (TJ to Goodman, Instructions December 1811, GATC). As head gardener of Poplar Forest, Nace probably delivered items from the garden to the kitchen in the Wing of Offices (Proebsting 2012). The other enslaved peoples at Poplar Forest painted Nace in a different light. John Hemings complained on behalf of other slaves to Thomas Jefferson in a letter from 1821 describing how Nace would take the items from the garden and bury them in a sub-floor pit in his cabin. Although Nace argued that the bounty was to be used for the house, other enslaved residents witnessed him selling the provisions at market instead (John Hemings to TJ, Nov. 29, 1821, MHi). Unfortunately, we do not have Jefferson’s response to this letter and it is unclear how the allegation was addressed.

References

Bear, James A., Jr. and Stanton, Lucia C (editors). 1997. Jefferson’s Memorandum Books: Accounts, with Legal Records and Miscellany, 1767-1826. Volume II. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Betts, Edwin Morris (editor). 1944. Thomas Jefferson’s Garden Book 1766-1824: With Relevant Extracts from His Other Writings. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society.

Betts, Edwin Morris (editor). 1987. Thomas Jefferson’s Farm Book with Commentary and Relevant Extracts from Other Writings. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Brodie, Fawn M. 1974. Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Chambers, S. Allen, Jr. 1993. Poplar Forest and Thomas Jefferson. Little Compton: Fort Church publishers, Inc.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. 1997. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings: An American Controversy. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. 2008. The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Heath, Barbara. ND. Slave Life Brochure. Manuscript on file at Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest.

Proebsting, Eric. “Poplar Forest’s Ornamental Plant Nursery and Its Place within the Life and Landscapes of Thomas Jefferson.” Paper presented at the Middle Atlantic Archaeological Conference, Virginia Beach, VA. March 2012.

Stanton, Lucia. 2000. Free Some Day: The African-American Families at Monticello. Charlottesville, VA.: The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc.

Stanton, Lucia. 2012. Those who Labor for My Happiness: Slavery at Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press.

Sources of Letters

MHi : Massachusetts Historical Society, Jefferson Papers.

DLC : Library of Congress, Jefferson Papers.

ViU : University of Virginia, Jefferson Papers.

NcU : University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Trist Papers.

GATC: George Arents Tobacco Collection

Other References

Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello: The People of the Plantation

http://www.monticello.org/site/plantation-and-slavery/people-plantation

The Poplar Forest Department of Archaeology would like to thank The Cabell Foundation and the Roller-Bottimore Foundation for their support in funding the Wing Re-analysis project. We would also like to thank Anne R. Worrell, a long time Friend of Poplar Forest and former Chairman of the Board of Directors, for her contributions to this project as well as her continuous support of the museum.