Archaeology Blog

Piecing Together a Teapot

Imagine that you have a small mountain of puzzle pieces in front of you of all shapes, sizes, and colors. You don’t know how many puzzles are represented by the pile, you don’t know how many pieces go into each puzzle, and most pieces will be missing. This is cross-mending.

It is a rare thing to find whole objects at archaeological sites. The vast majority of the artifacts that we find are broken into small pieces. Cross-mending helps us determine the vessel shapes and varieties that were used by people in the past.

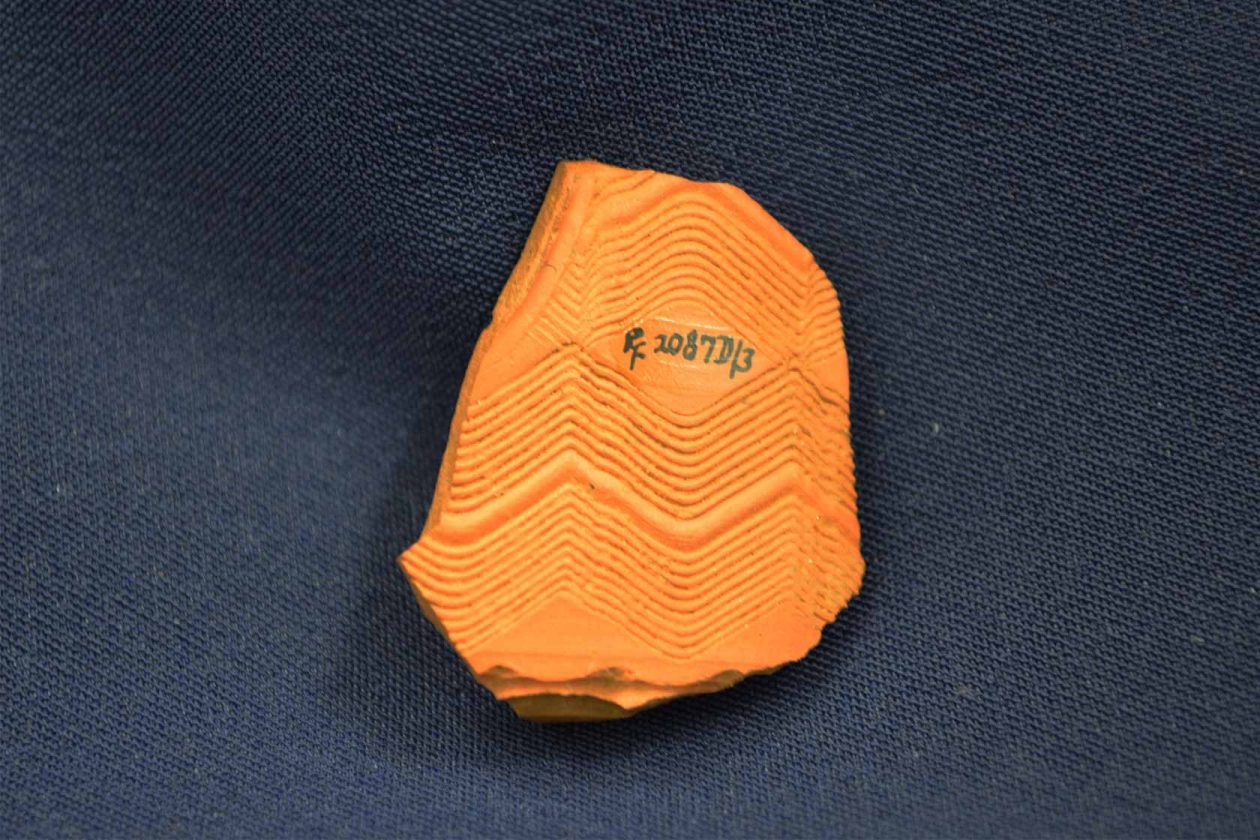

During the first stages of laboratory processing, artifacts are labeled using archival-stable lacquers and durable inks with their context number. This allows us to remove the artifacts from their storage bags without losing their provenience. All of the pieces of ceramic or glass are laid out on a table and separated by their type of ware, glaze, color, and decoration. Creating these narrowed groups helps control the potential chaos of cross-mending. When matches are found we temporarily fix them together using painter’s tape, which leaves no residue when removed. Eventually, the pieces will be adhered to each other using a special type of archival glue that can be easily dissolved without damaging the artifacts.

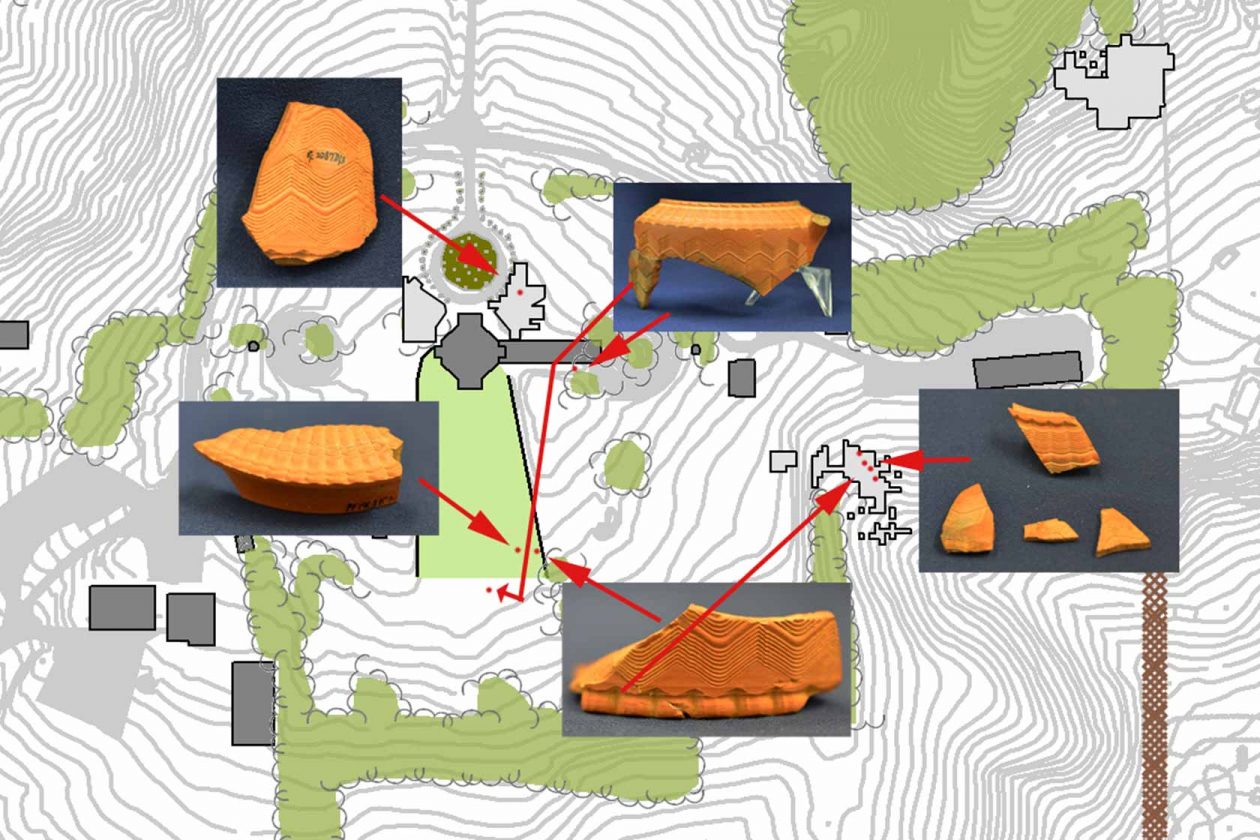

Cross-mending allows us to start to see vessels and reconstruct the tableware and storage containers that were used by historic households. It also allows us to discern how artifacts have been moved about in the soils. Human activities such as plowing, construction, planting, and other types of landscape modification can all shift artifacts from their original place of deposition.

Because archaeology has been ongoing for more than two decades here at Poplar Forest, we have many vessels in our collection that have been cross-mended by previous staff and student researchers. Cross-mending for the Clumps and Oval Beds restoration project was recently completed. While many identified vessels were only comprised of pieces from this particular area of Poplar Forest, a few matched previously identified vessels, such as this base sherd of rosso antico stoneware.

The first refined red stonewares made in Europe were produced in the Netherlands based on similar wares imported from Yixing, China. Production of “red porcelain” in England began in the late seventeenth century at John Dwight’s pottery kilns in Fulham (Hume 1982:120). A similar dry-bodied (meaning unglazed) stoneware was produced by the Elers brothers in Staffordshire around the same time. Dwight attempted to sue the Elers, who were Dutch immigrants, for stealing his production methods. The Elers brothers produced a successful line of refined red stonewares inspired by the earlier Chinese counterparts, examples of which can be found at the Victoria and Albert Museum here and here. Despite Dwight’s early success, many dry red-bodied stonewares are referred to as “Elers-type” ware. Both the Elers brothers and Dwight ceased production of this ware in the early 18th century and very few true Elers and Dwight vessels are found on American sites. Refined red stonewares were revived in the mid-18th century and by the 1760s Josiah Wedgwood was producing an engine-turned variant. Wedgwood called his red stoneware “rosso antico,” and despite his reluctance to produce it (Burton 1992:58-59; Copeland 2004:16) rosso antico became poplar for tea and coffee vessels (Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab 2002). Wedgwood produced rosso antico until the early nineteenth century. Many of his motifs were Egyptian inspired, sometimes incorporating sprig decorations in a similar type of black dry-bodied stoneware known as “black basalt.”

Rosso antico stoneware was imported to the Americas from England and has been found on a range of sites. The Florida Museum of Natural History has a few photos of examples found in Spanish colonial regions. A little closer to home, fragments found at the Mount Pleasant plantations are strikingly similar to ours in shape and decoration of the teapot body. The lid, however, is quite different from ours with relief designs, including a Tudor Rose (which seems apropos this week with the news related to the discovery of King Richard III coming from the University of Leicester).

Jefferson also used rosso antico teapots at Monticello. A similarly decorated lid was found in the West Kitchen Yard near the South Dependency Wing.

Our rosso antico sherd is decorated with a zig-zag pattern using an engine-turned lathe and is lead glazed on the interior. It was found about five feet south of an oval-shaped flower bed that was discovered during recent excavations. In his Planting Memoradum Jefferson indicated that dwarf roses were planted in this bed (November 1, 1816, ViU).

As you can see, this sherd mends to a previously identified vessel from our study collection. This vessel, a teapot, consists of eleven sherds from ten different contexts from the front of the house, the Wing of Offices, Site B, and the South Lawn.

The largest fragment from this vessel comes from the Wing of Offices. Partially burned, this sherd is from the shoulder and top opening of the teapot. It was found in a layer dating to the destruction of the wing. This sherd has been mended to another burned fragment from the South Lawn in a layer above planting stains. Three additional sherds were found in the South Lawn: two from the teapot lid and one from a base sherd.

The remaining sherds were found in various layers associated with the plant nursery (Site B). Jefferson’s ornamental plant nursery is located about 300 feet to the southwest of the Wing of Offices. This area was under cultivation until the late 1700s and was modified by enslaved workers to create an ornamental plant nursery in the early 1800s. Excavations have uncovered several nursery-related features such as a filled-in gully, planting stains, a stone drain, and drainage beds (Gary, Proebsting, and Lee 2010). Soils excavated in this area were artifact-rich, indicating that Jefferson utilized gardening practices suggested by contemporary manuals, which recommended gathering household debris and other types of refuse to help break up and fertilize clay-rich soils. George Washington also applied these recommendations at Mount Vernon, having various types of refuse gathered from around his plantation and added to the stercorary to make compost (Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association 2013). Wine bottle fragments found at William Paca’s Wye Island Garden (Leone, Harmon, and Neuwirth 2005) and Williamsburg (Brown and Samford 1990) are other examples of how these practices were utilized to create improved garden soils in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The dispersal of these teapot fragments allow us to reconstruct the movements of soils throughout Jefferson’s ornamental landscape. After its initial breakage, sherds of the teapot were incorporated into the plant nursery as part of soil enrichment. They were subsequently dispersed around Jefferson’s retreat in various ornamental planting episodes in the northeast corner of the main house and the east bank of the sunken lawn.

If you’d like to read more on our cross-mending analysis, check out our online Site B vessel exhibit.

References

Brown, Marley R. and Patricia M. Samford. 1900. “Recent Evidence of Eighteenth Century Gardening in Williamsburg, Virginia. In Earth Patterns, William Kelso and Rachel Most, editors. Pp 103-121. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

Burton, William. 1922. Josiah Wedgwood and His Pottery. London: Cassell and Company.

Copeland, Robert. 2004. Wedgwood ware.

Gary, Jack, Eric Proebsting, and Lori Lee. 2010. “Culture of the Earth”: The Archaeology of the Ornamental Plant Nursery and an Antebellum Slave Cabin at Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest. Forest: Thomas Jefferson’s Poplar Forest.

Hume, Ivor Noël. 1982. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Leone, Mark P., James M. Harmon, Jessica L. Neuwirth. 2005. “Perspective and Surveillance in Eighteenth-Century Maryland Gardens, Including William Paca’s Garden on Wye Island.” Historical Archaeology 39(4):138-158.

Maryland Archaeological Conservation Lab. “English: Dry-Bodied.” http://www.jefpat.org/diagnostic/ColonialCeramics/Colonial%20Ware%20Descriptions/English-Drybodied.html

Mount Vernon Ladies Association. “History: The Structure.” http://www.mountvernon.org/visit-his-estate/preserving-his-estate/archaeology-projects/repository-dung/history

ViU : University of Virginia, Jefferson Papers.