Archaeology Blog

“Take heede when ye wash”: Laundry at Poplar Forest

Karen E. McIlvoy

Who does the laundry in your house? Do you have a machine? According to the most recent statistics, almost 78% of laundry in the US is done by female household members. Today’s modern conveniences allow a single load of laundry to be completely cleaned and dried in about 90 minutes, but laundry in the 1800s was an arduous process that took days to complete.ˡ Research at Poplar Forest is currently exploring a possible laundry room in the Wing of Offices, trying to better understand the enslaved female labor that helped the plantation operate.

While he was never a full-time resident, Thomas Jefferson regularly visited Poplar Forest after he retired from the Presidency in 1809. He added a Wing of Offices to the east of his retreat home by 1816, consisting of four rooms in a row connected by a covered walkway along the south side. It was demolished and replaced in the 1840s, but was reconstructed following architectural and archaeological evidence in 2009 and is now a main part of the visitor experience at Poplar Forest.

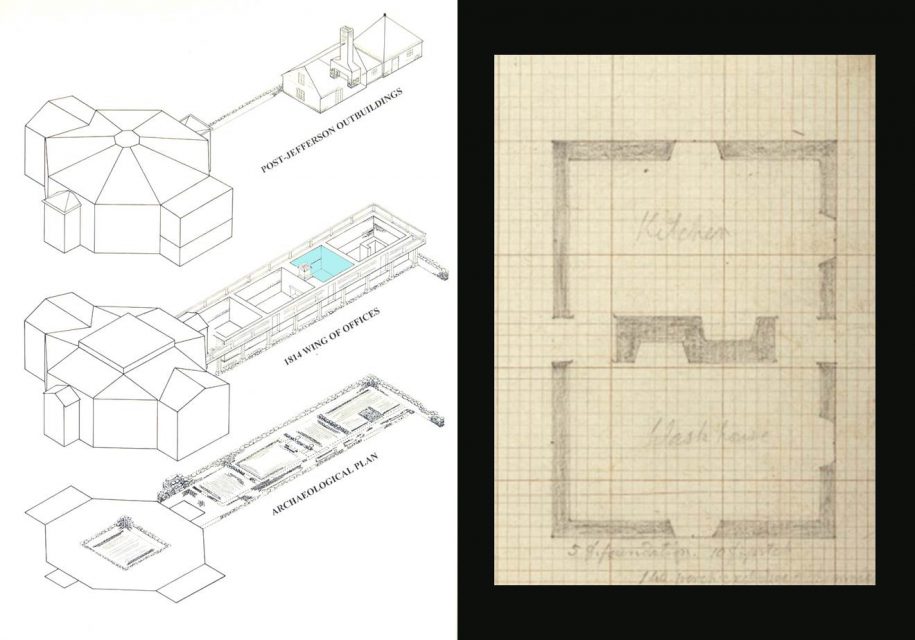

Figure 1: Chronological representation of the Wing of Offices site with the third room in blue (left). Jefferson’s original design for Kitchen/Wash House building at Poplar Forest, 1805 (Poplar Forest: dependencies (plan), circa 1805, by Thomas Jefferson. N261; K196 [electronic edition]. Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive. Boston, Mass. : Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003. http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org/)

The second and fourth rooms in the Wing have been identified as a kitchen and smokehouse, respectively. However, the functions of the first and third rooms are more ambiguous. The third room in the Wing has long been interpreted as a possible laundry room, based largely on indirect correlates with Monticello, draft architectural sketches from Jefferson’s papers, and architectural remains found within the Wing footprint.² But a deeper examination of archaeological remains may shed some light on this possibility.

Laundry is a prosaic and ubiquitous chore, so discussions of it have always been infrequent in the historical record. This has unfortunately led to the false impression that people in the past didn’t wash their clothes. This is simply untrue. Examining various account books, sermons, legal regulations, and housewifery guides published in the 18th and 19th centuries, three things become very clear: 1. laundry occurred more regularly than popularly imagined, 2. washing clothes has always been considered “women’s work”, and 3. laundry was generally an onerous, loathsome, and time-consuming chore that women hated.

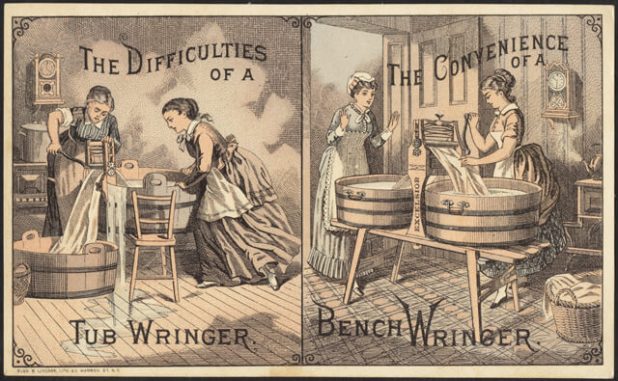

For example, simply getting started was hard enough. An average day of laundry required about 180 pounds of firewood and each ‘load’ could use 30-50 gallons of water. If the water had too high a mineral salt content, then it would react with the soaps and leave a scum on the cloth, so it had to be either collected from the right source or neutralized in advance. Metal pots were used to heat water and boil clothes, but water, heat, and acidity all cause mineral iron to leach out of iron vessels, contaminating the water and staining the clothing. Thus, washerwomen had to take care to use large copper or tinned kettles instead.

Figure 3: "The difficulties of a tub wringer. The convenience of a bench wringer." Advertising card, 1870-1900 (Boston Public Library). (http://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/7m01c3047) (left). Children posing with wash kettles of various sizes, Thornhill Plantation, Greene County, Alabama, Alex Bush, 1934 (right).

Once all the resources were prepared, the laundress could proceed with sorting, soaking, scrubbing, treating, boiling, bluing, bleaching, starching, wringing, drying, ironing and repairing the clothes. Each stage of laundry had many variations in equipment, methods, and details depending on the habit of the woman in charge. One woman might perform a step usually omitted by another or the day’s wash might not contain any items requiring a specific step. But despite the idiosyncratic nature of the details, the basic process was universal and did not change until the invention and spread of the modern washing machine in the mid-20th century.³

When looking at a possible laundry area, three main factors must be considered: location, architecture, and artifacts. Easy access to a source of acceptable water was crucial. Just as important was a way to dispose of that water along with soap, bleach, and ashes at the end of the day. An average wash kettle was 24 inches in diameter and weighed 70 pounds when empty. Such a vessel needed a large fireplace if not an open fire in the yard. Other features to consider are a solid brick or stone floor to reduce the chance of dust in the air, good ventilation to release steam and heat and allow air flow around drying garments, and a good drainage system to prevent water from pooling. Artifacts from the actual steps of the laundry process are clearly ideal for interpreting that activity, but the objects most likely to be archaeologically recovered are buttons and other clothing fasteners.

So how does the interpretation of the third room in the Poplar Forest Wing of Offices as a laundry room stand up to scrutiny?

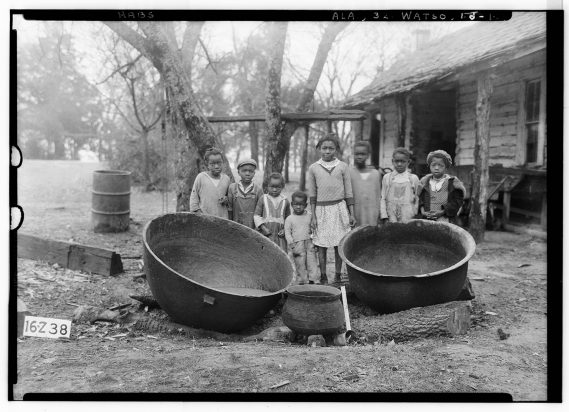

Figure 4: c.1809 map showing location of Poplar Forest retreat house in relation to Tomahawk Creek and Jefferson’s Spring (left). Base of stone fireplace facing east into the third room of the Wing of Offices (above). Brick floor extending out from hearth (below).

Several streams crisscross the property, so getting water has never been difficult at Poplar Forest. The house is located centrally between two branches of the Tomahawk Creek and only about 400 feet east of what is historically called Jefferson’s Spring. This was the main source of water for the house until the late 20th century.

Excavations inside the Wing uncovered back-to-back hearths in the second and third rooms. The hearth facing into Room 3 was six feet across and built from heavy stones, making it suitable for the hotter fires required to boil wash water and heat irons. Extending outward was a floor of handmade bricks laid in a straight soldier course. Foundations also showed a door on the south wall.

Figure 5: Map of Wing of Offices and Sunken Lawn excavations showing intact sections of Jefferson era French Drain (left). Photograph of exposed portion of French Drain (right).

Several sections of a French Drain were uncovered running east-west across the southern face of the Wing before veering south along the inside edge of a sunken lawn. Although it was most likely intended to catch rainwater dropping from the Wing’s roof, it demonstrates the awareness of drainage as an important matter in the area.

Figure 6: (left) Overview photograph of Wing of Offices excavations 1989-1991 (center). A sample of buttons in the Wing collection (sides). (Right) Distribution of shell buttons, representative of the Jefferson-era occupation of the Wing of Offices (above). Distribution of china buttons, representative of post-Wing occupation of the site (below).

Buttons are a great artefactual stand-in for laundering. Laundry was hard on clothes. After being soaked, scrubbed, beaten, stirred, hauled, hung, and ironed, garments regularly got damaged. Buttons were particularly susceptible. Although collection biases from excavations in the 1980s and 1990s limit our ability to consider this sample a full representation of the data, a total of 202 buttons were recovered from the Wing of Offices.

Two years after Jefferson’s death in 1826, Poplar Forest was sold to the Cobbs family. Their daughter, Emma, married Edward Hutter in 1840 and their family owned or occupied the property for the next 106 years. The Wing of Offices was still functioning during the Cobbs period of ownership, but it was torn down and replaced by two smaller buildings in the 1840s. The Wing buttons reflect the changes in laundering that may have taken place during this time.

The highest concentration of buttons associated with Jefferson-era occupation contexts is located in the eastern end of the interior of the Wing footprint. The majority of the buttons included in this distribution are made from copper alloy or bone. However, the spatial distribution of shell buttons suggests that this sample is contemporaneous to the Jefferson era of occupation. Of the sixteen shell and mother-of-pearl buttons recovered from the Wing, only two of them were found outside the footprint of the original structure and those inside clustered very tightly around the footprint of the third room.

In contrast, the buttons datable to the Hutter-era occupation cover the majority of the yard area to the south with only a small concentration within the later kitchen structure. Given the assumption that buttons can be equated with laundering activity, the distribution maps suggest that laundry was done mainly inside the Wing of the Offices until it was destroyed and replaced, at which time the bulk of laundering activity moved outside. The Wing stood during a time when the house was more lightly occupied; first Jefferson and his granddaughters only sporadically visited and then the Cobbs family consisted of only three people. With less laundry to be washed, a single room would be sufficient space and the laundress would not have to risk rain, wind, or dirt to complete her task. However, Emma and Edward Hutter eventually had eleven children and her parents living with them full time. Fifteen people produced a lot of dirty clothes; more than can be comfortably done in one room, especially once reduced in size and combined with cooking space.

In summary, the third room in the Wing of Offices meets all three of the archaeological requirements for a laundry area: the location is within easy access to a good water source, the room itself is architecturally designed for laundering functionality, and the archaeological remains of over 300 clothing-related artifacts were recovered including thimbles, buckles, cufflinks, straight pins, eyelets, corset busks, and buttons. The evidence is not strictly scientifically conclusive, but it does suggest that the interpretation of Room 3 as a laundry room is sound.

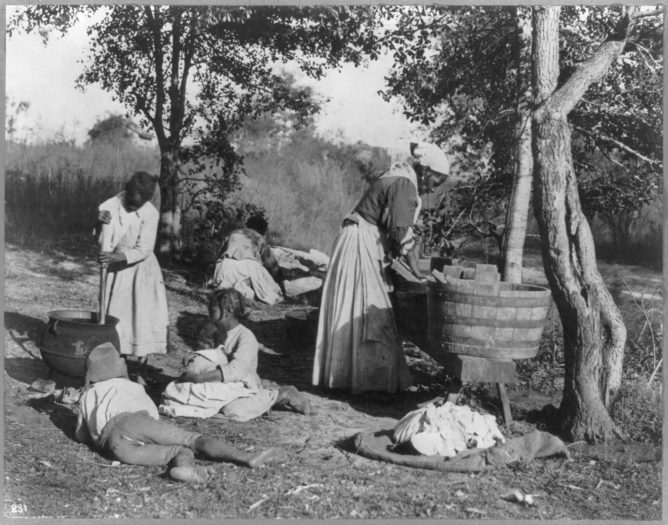

Figure 6: African-American woman doing laundry with a scrub board and tub, girl stirring pot with 3 other children on the ground watching, and a woman in the background spreading laundry, c.1900 ((LOC) http://www.loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a51106/).

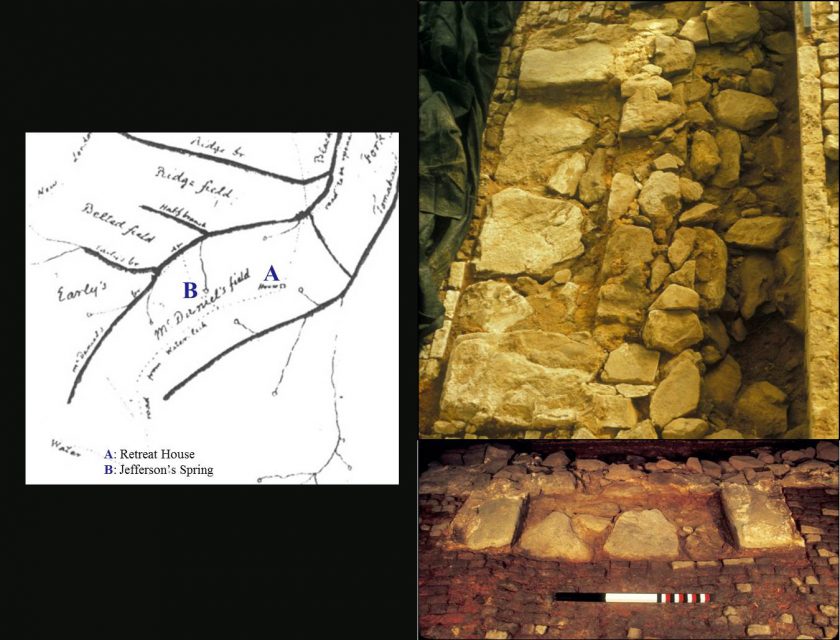

However, it is important not to focus so much on the laundry that we forget the laundress. A plantation laundry room was a black labor space. Jefferson’s housekeeper, Hannah, may have been in charge of a few young enslaved women working in the laundry room in the Wing of Offices. Despite their vital contributions to the functioning of a plantation household, enslaved washerwomen have been “generally consigned to the rearguard of the female labor force, where they occupy a shadowy, often marginal position”.4 Laundresses inhabited the liminal realm between the public and private: they facilitated the family’s image of cleanliness and domestic purity by literally interacting with the filth and grime of the physical world.

“Relegated to this invisible but necessary realm, laundry thus bears the weight of the contradictory conjunction between cleanliness and dirt, appearance and effacement, the private and the public…Dirt’s banishment is a mysterious enactment, laundresses over time practicing an obscure if challenging magic. In just this fashion have women in domestic service been relegated to the back door, their presence and their work erased to serve appearances, socioeconomic considerations, and sheer snobbery.”5

Perhaps by reexamining the laundry room at Poplar Forest, we can begin to give enslaved washerwomen the credit they deserve.

References:

- Private Label Manufacturers Association “Primary Responsibility for Household Chores”, October 2012. Private Label Manufacturers Association “Washes per Week of Washing Machines in 2014, by region”. Statista, accessed February 2017.

- Thomas Jefferson Papers: An Electronic Archive. Boston, Mass. : Massachusetts Historical Society, 2003. http://www.thomasjeffersonpapers.org/

- For more detail on the historic laundry process, the following housewifery guides are available for free through Google Books:

1557 Thomas Tusser, Five Hundred Points of Good Husbandry.

1739 E. Smith, The Compleat Housewife: or, Accomplish’d Gentlewoman’s Companion.

1825 John Armstrong, The Young Womans Guide to Virtue, Economy, & Happiness.

1830 Esther Copley (nee Hewlett), Cottage Comforts, with Hints for Promoting Them, Gleaned from Experience, Enlivened with Authentic Anecdotes.

1844 Thomas Webster, An Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy.

1850 Eliza Leslie, Miss Leslie’s Lady’s House Book; a manual of domestic economy.

- Carole Rawcliff, “A Marginal Occupation? The Medieval Laundress and her Work,” Gender and History 23, no. 1 (2009): 147.

- Aretha Aritha van Herk, “Invisibled Laundry,” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27, no. 3(2002): 894.