Archaeology Blog

Under Lock and Key

Keys and lock parts are typical artifacts recovered during archaeological excavations around houses. As you might imagine the presence of these objects indicate attempts to secure belongings, people, or animals. A topic of research that we are addressing relates to the security of the Wing of Offices. From documentary evidence, we know that Thomas Jefferson’s retreat home at Poplar Forest was locked when it was not in use. While we are confident that the main house was secured, we are curious to know what security measures were taken in the wing. Examining the physical characteristics of locks and keys found during the excavations can help us begin to understand the methods used in safeguarding the wing of offices and its contents.

Beginning with documentary evidence, a surviving letter written by Jefferson’s granddaughter Cornelia colorfully describes a visit in which the party had been locked out of the main house:

When we arrived here we found Mr. Yancey gone to Liberty Court (16 miles off) and the keys of the house could not be obtained untill his return; Burwell had shaken open the front door so that we could enter & get into several of the rooms of the house but our chamber door in which room all the bedding was locked. Besides that, nothing either to eat or drink could be obtained, & to make the matter worse, the hard winter had killed almost everything in the garden. We satisfied our hunger with the wrecks of our travelling provisions, & whatever old Hannah & Burwell could find, after dilligently searching house & garden for several hours to collect the little that had been overlooked when the house was shut up last year, on the one hand & on the other, what the cold had spared. We were more hungry and tired than nice though, you may suppose, & at night were very contentedly about to stretch off upon the outside of the beds which had a single blanket tossed over the mattress, when the keys arrived, & in a moment we had tea & wine & comfortable beds. (Cornelia Jefferson Randolph to Virginia Jefferson Randolph April 22, 1821. UNC-Trist)

The inconvenience and discomfort felt by Jefferson’s family, and their willingness to write about it has provided some very important details about the state of the house. For instance, Cornelia’s use of the word “keys” indicates that there were multiple keys in use. She also identifies the keeper of those keys as Joel Yancey, an overseer of Poplar Forest. It is also helpful to know that the main house was not only locked from the outside, but specific rooms (and contents such as bedding) were also locked on the inside. Furthermore, Cornelia recounts that the house had been “shut up last year”, which allows us to infer that the practice of securing the house was a regular occurrence.

Objects that Secure

In archaeology, the presence of hardware items such as locks, hinges, straps, hooks, padlocks, and keys help to indicate security measures that may have been taken. Most of these pieces of hardware accompany doors; however gates, trunks, cabinets and other objects may have also been fashioned with locking mechanisms.

The wing of offices connects to the main house along the Eastern side, and the four individual rooms are accessed by doors along the southern exterior (the side of the sunken lawn). Stock locks and rim locks are two types of locks that we think were used on exterior doors of the main house and wing. Here we show an incomplete rim lock that was recovered from the excavations of the wing (Figure 4). Some of the interior components of this rim lock are made of brass, a practice that began in the 19th century (Priess 2000: 84).

For comparison, this is a reproduction of a complete rim lock used on the lower level of the main house at Poplar Forest:

Padlocks are useful because they are portable. Their variations in size and shape (including round, heart or half-heart, triangular, and square) help us to identify the time frames for when they were made and used. Larger padlocks could be used for doors, and smaller varieties would have been more useful for smaller items such as trunks. Padlocks in general have a simple locking mechanism and were susceptible to picking until improvements were made in the late 18th century (Priess 2000: 82).An escutcheon is the plate surrounding a

An escutcheon is the plate surrounding a key hole. While these are often decorative, escutcheons serve to frame the key hole and protect the surrounding area for when the key misses the keyhole. Some key holes contain a round pin inside (see figures 1 and 7) known as a drill pin. The key that fits this lock will have a hole in its post (figures 2 and 6) that fits around the drill pin in order to provide alignment and stability (Priess 2000: 79). A lock may also have a separate plate called a keyhole cover (see figure 1) that blocks or protects the key hole.

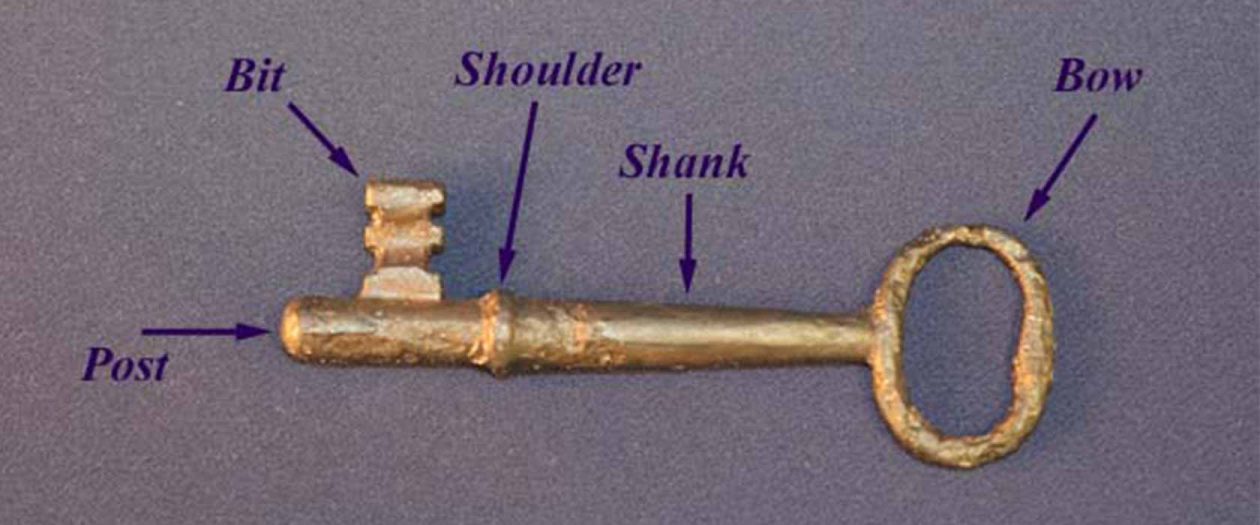

Obviously, a lock is useless without its key. The handle of a key, or bow, is one of the more decorative elements and varied in ornamentation and style over time. Extending from the bow is the key shank, the sizes of which varied in length and diameter. The shoulder helped position the key when placed into the lock, providing guidance and stability. The bit of the key interacted with the wards and tumbler to retract or extend the bolt of the locking mechanism. The post is the very top of the key, and it may have included a barrel hole or drill hole in the end (see figures 2 and 6). The drill hole fits over the circular pin within the keyhole (figure 7). Again, this feature is used to help guide the key and ensures that the correct key is used for that particular lock.

What to Protect?

The idea of security is fascinating because it raises several questions about daily life in the past. What items are being locked up, whom do they belong to, and who are they being kept from? Objects protected in this way are given a value, whether monetary or sentimental, and can speak volumes about the people using them.In knowing that Joel Yancey held the keys to Poplar Forest, he would have had control over the contents of locked rooms and would have been able to lock and unlock them at his discretion. At Monticello, Jefferson’s granddaughters were taught domestic responsibilities. As a mistress of the house, “each daughter took a turn as house-keeper for a month at a time, carrying the keys to locked storerooms, choosing menus, and more” (Stein 2002: 55). It is likely that the granddaughters would have exhibited this responsibility during their visits to Poplar Forest as well.

In knowing that Joel Yancey held the keys to Poplar Forest, he would have had control over the contents of locked rooms and would have been able to lock and unlock them at his discretion. At Monticello, Jefferson’s granddaughters were taught domestic responsibilities. As a mistress of the house, “each daughter took a turn as house-keeper for a month at a time, carrying the keys to locked storerooms, choosing menus, and more” (Stein 2002: 55). It is likely that the granddaughters would have exhibited this responsibility during their visits to Poplar Forest as well.Thomas Jefferson’s account log shows that he purchased one bookcase lock at a cost of 3 dollars (Account with Reuben Perry, 1811. ViW). As an avid reader and book collector, he had a locked Book Room at Monticello (Stein 2002: 42). Considering how passionate he was about books, it makes sense that he would keep some of his most prized possessions under lock and key.

Thomas Jefferson’s account log shows that he purchased one bookcase lock at a cost of 3 dollars (Account with Reuben Perry, 1811. ViW). As an avid reader and book collector, he had a locked Book Room at Monticello (Stein 2002: 42). Considering how passionate he was about books, it makes sense that he would keep some of his most prized possessions under lock and key.

In traveling, it was common practice for personal items to be placed in trunks or cases. For instance, Jefferson’s copying press, polygraph machine, and case that held drawing instruments all contained small keyholes on their exteriors (Stein 1993: 367-371). In addition to preventing items from being stolen, trunks would also be locked as a way of securing the contents so that they did not fall out during transport. While he traveled, Jefferson would have likely been equipped with his “dinner canteen”. A canteen was a box or set of boxes that held items for portable dining such as cutlery and dishes (Stein 1993: 318). This idea is similar to the use of picnic baskets today.

Larger stores of food would have been locked away in order to ration them. Thomas Jefferson wrote about the need for locking up provisions: “I know that neither people nor horses can work unless well fed, nor can hogs or sheep be raised. but full experience here has proved that 12. barrels for every laborer will carry the year through if kept under lock & key” (TJ to Goodman Dec 23, 1814. NYPL). Here Jefferson refers to rationing barrels of corn. We know that the Wing of Offices held a kitchen and a smokehouse, and possibly a storage room. It is reasonable to assume that any food items stored within the wing would have been locked away in order to control access to them.

As we examine the keys and locks from the wing we can start to think about the activities that were used to keep items secure. At the most basic level, we can tell from the presence of rim locks and stock locks that the doors of the wing were locked. Padlocks found during the excavation of the wing, along with documentary evidence, reveal that contents within rooms may have also been locked as an additional measure of security. After analyzing the locking mechanisms that were put in place as safeguards, we can begin to broaden the scope of research to inquire about the items that were being protected, and the persons who were allowed or denied access to these material goods.

Sources of Letters

MHi : Massachusetts Historical Society, Jefferson Papers.

DLC : Library of Congress, Jefferson Papers.

ViU : University of Virginia, Jefferson Papers.

NcU : University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Trist Papers.

NYPL : New York Public Library, George Arents Tobacco Collection

References

Hume, Ivor Noel. 1969. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. New York: Alfred Knopf, Inc.

Priess, Peter J. 2000. “Historic Door Hardware.” In Studies in Material Culture Research, edited by Karlis Karklins, 46-95. The Society for Historical Archaeology.

Stein, Susan R. 1993. The Worlds of Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Stein, Susan R. 2002. “A Look Inside Monticello.” In Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, edited by Beth L. Cheuk, 41-69. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc.

The Poplar Forest Department of Archaeology would like to thank The Cabell Foundation and the Roller-Bottimore Foundation for their support in funding the Wing Re-analysis project. We would also like to thank Anne R. Worrell, a long time Friend of Poplar Forest and former Chairman of the Board of Directors, for her contributions to this project as well as her continuous support of the museum.