Jefferson’s Response to the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

Jefferson’s Response to the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793

By Karen Warren

Plagues. Epidemics. Pandemics. These are frightening occurrences that the world has not been able to avoid. They emerge quietly by attacking a few victims at first. No one is really concerned. People’s thoughts are “it’s just another bug that will come and go.” Then something happens, it doesn’t go. All of a sudden, as if overnight, the illness charges its way through a city or town forcing itself upon the most vulnerable citizens first, then the rest. Now, everyone is responding in one way or another. It may be fear or it may be to fight the illness by taking strict precautions, like we are doing now with COVID-19. In 1793 the citizens of Philadelphia, our nation’s capital at the time, were facing the same struggle with a yellow fever epidemic. Some feared for their lives because they couldn’t leave town the way some of their more fortunate neighbors were able to. However, Thomas Jefferson did not appear to be afraid as he remained to continue his work as Secretary of State. He did appreciate the severity of the situation. His response was a scientific analysis approach in which he recorded his observations of the epidemic’s traits, the mental and physical effects on the citizens, and a plan to prevent its rapid spread in the future.

Yellow fever strikes its victims with chills, purple marks on the skin, jaundiced (yellow) eyes and skin, and black blood-filled vomit. It lasts about one week to ten days for those whose constitutions are strong enough to fight. The mosquito Aedes Aegypti is its carrier. This species lives in subtropical or tropical areas and most likely made its way to Philadelphia in barrels of stagnant water on shipping vessels. It then bred in the freshwater barrels throughout the city. Dr. Benjamin Rush, while observing anything unusual happening during the outbreak, noted that “moschetoes” were “uncommonly numerous” that year.

With no clear understanding how the illness was spreading, nor how to accurately fight it, the citizens of Philadelphia began to panic. Jefferson noted on September 1 that “everybody who can is flying from the city, and the panic of the country people is likely to add famine to disease.”1 President George Washington and Henry Knox, Secretary of War, were among those leaving the city. Alexander Hamilton fled as well but not before contracting yellow fever himself. Jefferson stayed, however, feeling a sense of duty to continue working, “I have withdrawn my daughter from the city, but am obliged to go to it everyday myself.”2 He felt that “there might be serious ills proceed from there being not a single member of the administration in place.”3 As a leader, Jefferson wanted to portray calm in the midst of the panic so as not to further the fear of his constituents, “I would really, go away, because I think there is rational danger, but that I had before announced that I should not go till the beginning of October, & I do not like to exhibit the appearance of panic.”4

While Jefferson worked as statesman, the researcher in him was also at work keeping a keen eye on the horrific scene unfolding around him. He accurately identified the symptoms of yellow fever, “with a pain in the head, sickness in the stomach, with a slight vigor, fever, black vomit and feces, and death from the second to the eighth day.”5 He was concerned that, “it is of the opinion of the physicians there is no way of stopping it…no two agree in any part of their process of cure.”6

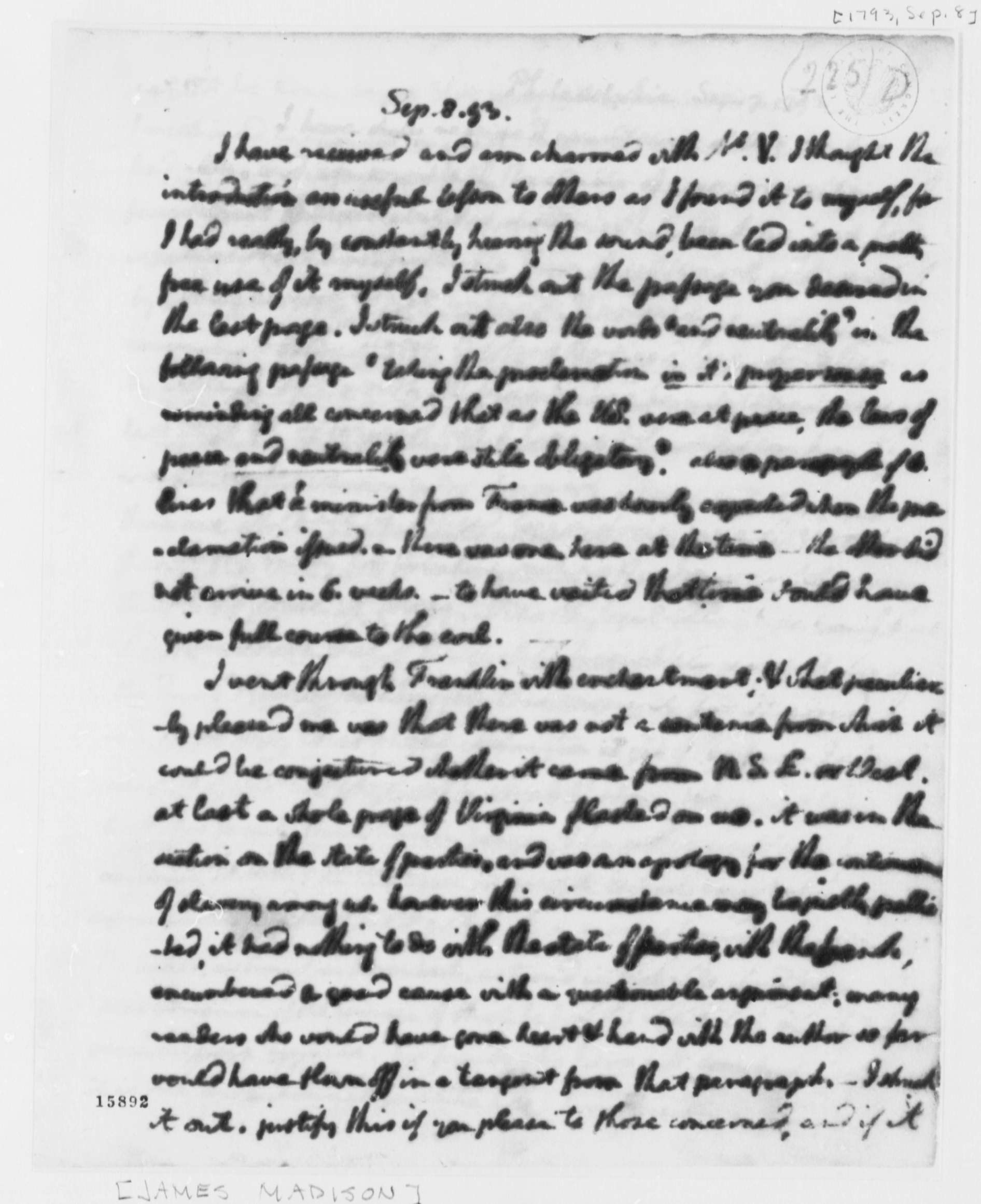

Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 8, with Fragment Copy. -09-08, 1793. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib007979/

Photo: Library of Congress

As the death count increased, Jefferson made note of the numbers and relayed them on occasion to James Madison and a Mr. Morris, “About seventy people died of it two days ago…”7 and “The deaths under it, the week before last were about forty, the last week fifty, this week they will probably be about two hundred and it is increasing.”8 Jefferson’s prediction that the deaths would keep increasing was accurate. The final death count was five thousand citizens. In a city of fifty thousand that is 10% of the population.

Jefferson and Maria left Philadelphia earlier than Jefferson had planned. By mid-September the threat of contagion was high so they set out for Monticello and stayed until the end of October, when yellow fever cases started to decrease. Jefferson met Washington in Baltimore and they traveled together to Germantown to await the end of the illness. The first frost in November ended mosquito season and the cases of yellow fever were diminishing: “the fever in Philadelphia has almost entirely disappeared…the inhabitants, refugees, are now flocking back generally.”9 Jefferson and Washington moved back as well.

Even with his keen observation and analytical skills, Jefferson did not recognize that the epidemic ceased when mosquito season ended. Instead he focused on the miasma, or “bad air,” theory, which was still the case in 1805 while he was president. A yellow fever epidemic had struck New York City in 1803 and afterwards Jefferson continued to analyze the illness as he noted that, “the yellow fever is generated only in low close, and ill cleansed parts of a town,”10 Still thinking that miasmata was the cause, Jefferson came up with a massive social distancing plan11. He decided that it was “practical to prevent its [yellow fever] generation by building our cities on a more open plan.”12 The plan went as such: “Take for instance the chequer board for a plan. Let the black squares only be building squares and the white ones be left open in turf & trees. Every square of houses will be surrounded by four open squares & every house will front an open square.”13 His reasoning was so that “the atmosphere of such a town would be like that of the country, insusceptible of the miasmata which produce yellow fever.”14

In the midst of a yellow fever epidemic Jefferson shows consistency of character. He is ever the observer and analyzer trying to figure out why something is and how to make it better. This situation was no different. He saw an illness destroying his neighbors, wanted to know how it was infecting them, and proposed a plan that he felt could help prevent such a massive spread for future generations. Had his development plans been heeded there is the possibility that the epidemics this country has suffered may have been less threatening.

1 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 1, 1793

2 Ibid

3 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 8, 1793

4 Ibid

5 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison September 1, 1793

6 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 8, 1793

7 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 1, 1793

8 Thomas Jefferson to Mr. Morris, September 11, 1793

9 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, November 9, 1793

10 Thomas Jefferson to Constantine Francois Chasseboeuf Volney, February 8, 1805

11 Ibid

12 Ibid

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

Bibliography

Meacham, John. The Art of Power, Random House Trade, New York, 2013

Jefferson, Thomas. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson: Correspondence, cont. Vol.4, edited by Taylor and Maury, 1854

Jefferson, Thomas. Thomas Jefferson: A Chronology of his Thoughts, edited by Jerry Holmes, Rowman & Littlefield, 2002

Jefferson, Thomas. Memoirs Correspondence and Private Papers of Thomas Jefferson Edited by Thomas J. Randolph, Vol.3, Oxford University, 1829

Jefferson, Thomas. Jefferson’s Germantown Letters Together with Other Letters Relating to his Stay in Germantown During the Month of November, 1793, edited by Charles Francis Jenkins W.J. Campbell Publishers, 1906

Jenkinson, Clay. Thomas Jefferson, Epidemics, and his Vision for American Cities, governing.com/context/Thomas-Jefferson-Epidemics-and-his-Vision-for-American-Cities.html April 1, 2020

Abrams, Jeanne. Death Stalks the Capitol, historynet.com/death-stalks-the-capitol.html